Review by Amanda Bennett, PhD

Publisher: Grieveland Press, 2021

Length: 100 pages

Grief is an offering none may refuse. When I was 26, my best friend died suddenly under mysterious circumstances. It was days before we knew she passed. Still lodged in the deep isolation of COVID-19 quarantine, I mourned her death mostly alone through my poetry. I wrote poems to her ghost out of a desperate need to hear her voice in whatever form it chose to present itself. When I spoke I wrote her voice in italics, to distinguish hers from mine. I came to call her my familiar, a term witches use to describe an aide who appears to help them come into their powers. The time I spent grieving her death taught me to live as a vessel or medium through which untold stories could make their inevitable return into the world. I learned to live as a vessel for the spirits through closely studying the presence of Afrodiasporic spiritual traditions within the work of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, whom I respectively interpreted as a griot and a medium in my dissertation, Developing a Vocabulary of Feeling: The Spirituality of Black Feminist Self-Repair. Within West African culture, griots are gifted oral storytellers who are responsible for memorizing and performing the history of their community through mediums such as music and poetry. Morrison acted as a griot not only through writing novels such as Beloved and The Bluest Eye, but also through her work as an editor at Random House during the 1970s, where she facilitated the publication of Black history texts such as The Black Book, autobiographies of Black activists and intellectuals such as Angela Davis and Muhammad Ali, and the creative work of Black writers such as Henry Dumas, Toni Cade Bambara, and Gayl Jones. Walker acted as a medium throughout most of her life, after a traumatic childhood accident gave her what Black feminist literary scholar Thadious Davis describes as a “second sight.” This second sight allowed Walker not only to connect with the ghost of Zora Neale Hurston and help revive her literary legacy, but also to catalyze her deep capacity for empathy into activism on behalf of oppressed people in the United States and around the world.

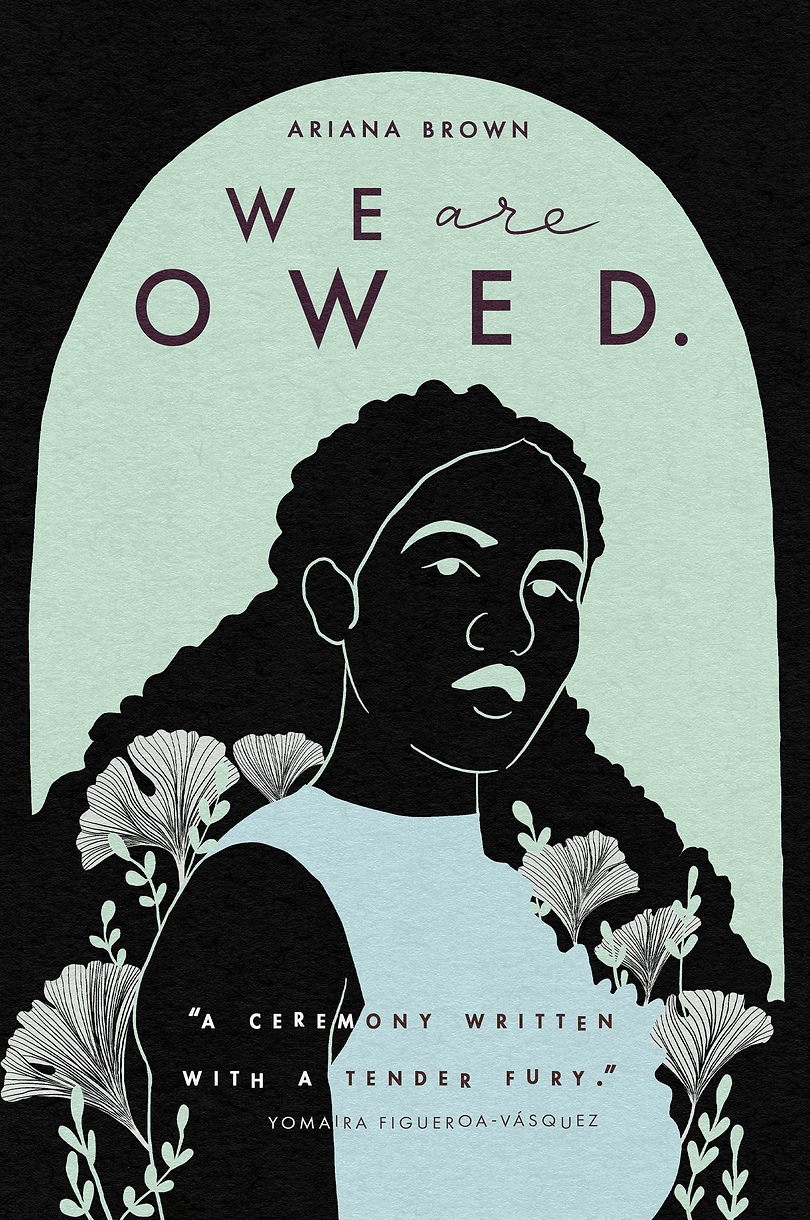

In her debut full-length poetry collection, We Are Owed., Ariana Brown steps into her own inheritance as a griot and medium as she weaves together vignettes of her experiences mourning the death of her father in a 1992 military accident, growing up on the periphery of Mexican culture as a queer Black Mexican-American person, connecting with the ghost of the Black revolutionary Yanga, and navigating her relationship to the Spanish language, which belongs both to her grandmother and the conquistadors who colonized her people. In the intricate tangle of these stories there is no distinct beginning, nor is there a clear boundary between Brown and the stories she tells. In We Are Owed.’s final poem, “Inhale: the Ceremony,” the speaker states “There was never/any magic; there/was never this/body or its wound,/there was only/water/& the stories/we passed/through it” (93). In surrendering both her body and its wound, Brown’s speaker alchemizes herself into water, that fluid no-place where the “I” may finally disintegrate into an undefinable “we.” It is this wild promise of becoming a “we” that lives in excess of borders, anti-Blackness, and legacies of colonial violence that structures the flow of Brown’s body of water in We Are Owed.

Brown’s practice of passing stories through water falls within a longer genealogy of Black women writers, specifically Toni Morrison. In her essay, “The Site of Memory,” Morrison writes

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our “flooding” (1995, 99).

The poems in We Are Owed. feel as if Brown is calling upon the flood of her memory to route her back to her original place, regardless of where or when that may be. In doing this, Brown troubles the notion that memories are things which must be experienced first hand; instead, they may be recollections that are inherited across generations or are ingrained into the buildings, relationships, and cultural norms that produce our everyday reality. For example, though Brown’s father passed away before she was born, she describes him being “conjured/by Otis Redding & my mother’s voice” (16). Alternatively, in “A Division of Gods,” Brown writes “while visiting Templo Mayor in Mexico City, I reckon:/walking the same land Cortés did/walked/tried to own./in the shadow of his Cathedral,/I shudder./Templo Mayor is now a museum./are there records of Black people/visiting plantations and crying?” (52) In opening herself up to receive memories of her father from her mother and others who knew him, Brown develops her capacity to flood riverbanks that are not her own, meaning she allows herself to be perceptive enough to remember histories of colonial violence that its perpetrators would rather be left forgotten. In this sense, Brown is drawing a connection across centuries and borders between the American military enterprise that played a role in her father’s death and the Spanish colonial project that resulted in the murder and enslavement of thousands of people of African descent.

One of Brown’s greatest strengths in this poetry collection is her receptivity to porosity, a gift which places her in alignment with another iconic Black woman writer, Alice Walker. In the afterword to her seminal novel The Color Purple, Walker, describing herself as “author and medium” wrote, “I thank everybody in this book for coming” (1982 n.p.). Additionally, in the novel’s epigraph, Walker wrote, “To the Spirit: Without whose assistance neither this book or I would have been written” (1982 n.p.). Through these words Walker implies she channeled the voices that would later become the characters readers know as Celie, Shug Avery, and Nettie through her connection with an ambiguous entity called “Spirit,” a force which gave life to both the novel and its author. Walker’s identification of herself as a medium is significant not only because it draws on African and Black American folk traditions in which certain individuals are gifted with the power of conjurers or griots (oral storytellers), but also because it offers a template through which contemporary Black women writers may understand our unique ability to tap into experiences which are not directly our own. Brown’s porosity in We Are Owed. can be seen in her ability to connect her school’s mascot of the mustang to the colonial history of wild horses in the Americas, as well as the connection she draws between the inability of aguacate (avocado) to be used for the benefit of the Spanish colonial project and their place as a luxury food item within her family. In these moments of channeling histories that she did not immediately experience, Brown teaches her reader to be attuned to spirits or stories which live within everyday objects.

It is perhaps not unintentional that Brown ends and begins We Are Owed. with references to offering as a way to deepen relationships with other spiritual and living beings. In the collection’s first poem, “At the End of the Borderlands,” Brown’s speaker writes that “our blackness grow full from offering” (13). Later, the collection’s next-to-last poem, “Borderlands suite: North,” ends with the lines “Praying is not like wishing—you must/have something to offer” (91). Spiritually, offerings are performed as acts of devotion, worship, or gratitude to a god or a collective of ancestors. By placing these two moments of offering side by side, it is possible to expand the definition of offering to become a ritual that Black folks can perform with and for each other. The practice of offering allows us to become aware of the ways in which the Spirit (to use Walker’s language) flows through our ancestors, our work, and ourselves. This ceremony of acknowledging flow between multiple spheres of existence is what facilitates the flood of memory that Morrison describes. It is in this watery space of imagination that the dead return to us as guides or familiars who help us find the people with whom we are destined to be in community, an experience to which I can personally attest. I’d like to believe that the “we” of We Are Owed. is comprised of every Black person, dead or alive, who has a story that needs to be told. What we are owed is the offering of a voice. The offering that Brown makes in her collection is simply the first of many.

Dr. Amanda Bennett is a queer Black feminist facilitator, researcher, and poet. As an educator and storyteller, she cultivates innovative ways of using language and popular culture to guide people toward internal transformation, self-awareness, and social change. Amanda is the founder of define&empower, an education and consulting collective that supports companies and schools in reshaping their operating systems around ethical and inclusive principles. She outlines her framework for a queer Black feminist future in her poetry, essays, and short fiction, which have appeared on her Substack newsletter and in publications such as Obsidian, Jellyfish Poetry, Murder Journal, The Huffington Post, and The Atlantic.