Review by Jordan Ealey, University of Maryland, College Park, 2021

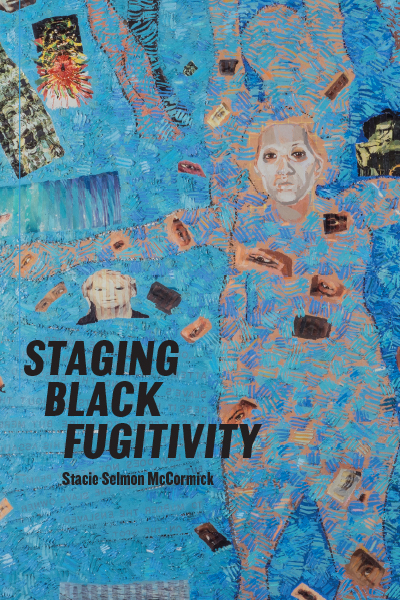

Publisher: Ohio State University Press , 2019

Length: 162 pages

Slavery’s legacies, afterlives, and remains continually haunt our present. Embedded in our political, cultural, educational, and social institutions, the specter of slavery is intimately entangled with contemporary life, functioning as an unresolvable enmity expressed toward black people. Studies of slavery within black theatre history are often relegated to the past, with many black theatre scholars looking to nineteenth-century black playwrights like William Wells Brown and Pauline Hopkins. Critical texts such as Bodies In Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910 by Daphne A. Brooks and The Captive Stage: Performance and the Proslavery Imagination of the Antebellum North by Douglas A. Jones are just two examples of the engagement of early works of black theatre and performance that stage and engage with slavery. Most recently, however, Modern Drama’s special issue, “Slavery’s Reinventions,” edited by Douglas A. Jones, creates a dialogue about black theatre in the mid-twentieth to twenty-first centuries regarding the usage of slavery in the theatrical imagination. The special issue rectifies a considerable dearth in theatre and performance studies, querying the disciplines to take seriously the employment of dialogues of slavery and freedom to stage and defamiliarize aesthetics and performances of blackness.

How, then, are slavery’s (re)inventions and afterlives reckoned with through aesthetics and performance? What is the efficacy of the theatrical form for black theatre makers to stage these fraught histories? Stacie Selmon McCormick’s Staging Black Fugitivity answers these questions through a critical investigation of twentieth and twenty-first century black playwrights and their dramatizations of slavery. McCormick’s project is animated by three central questions: “How does the return to slavery in contemporary black drama illuminate the current public discourse around blackness, freedom, and belonging? What becomes possible artistically and politically when we push against received histories of slavery (those narratives circulated across time that render enslavement and black experience in one-dimensional terms)? How can performances of these dramas enhance our capacity to represent the intricacies of the institution of slavery? (2). In four chapters and an epilogue, McCormick presents a case for a deep investigation of how black theatre and performance discusses the remnants of slavery, questioning “the tensions of American citizenship and the limits of black freedom” (5).

Through close readings and performance analysis, McCormick argues for fugitivity as a reading praxis for engaging slavery’s presence in contemporary black theatre in order to create new formulations for understanding black subjectivity. McCormick engages an impressive array of artists and playwrights such as Suzan-Lori Parks, Lorraine Hansberry, Amiri Baraka, George C. Wolfe, Pomo Afro Homos, August Wilson, Lydia Diamond, and Robert O’Hara, among others. This wonderfully rich ensemble activates diverse strategies for reading and engaging fugitivity as a narrative and performative modality in the myriad dramas she discusses. McCormick’s readings, thus, serve as “a starting point rather than a destination—like black fugitivity, constantly in motion” (13).

For McCormick, reading black drama in conversation with, as, and against the neo-slave narrative – and situating it in Afrofuturist, feminist, and queer frameworks – destabilizes the received histories of slavery, black performance, and black embodiment, and implores scholars and practitioners to sit in the discomfort of unknowability. McCormick not only focuses on a close reading of the text but also includes staged productions, playwright interviews, and marketing materials. McCormick’s formulation, “performances of fugitivity”—which are described as “subversive, radical, and experimental performances of black artistic and political freedom at the site of slavery” (5)—offers a grammar for critically considering both the form of drama and fugitivity’s location within it. Staging Black Fugitivity, then, unseats the temporal logics of slavery and fugitivity as “acts of world (re)-making for black subjects that take place on the contemporary stage” (18).

Performance limns the site of slavery visually, corporeally, sonically, and affectively, making it efficacious on multiple registers. In her book’s first chapter, “Mapping Fugitivity in Drama,” McCormick’s readings highlight this, as she presents four categories of fugitivity in black drama: revolutionary fugitivity, fugitive time, black feminist fugitivity, and black queer fugitivity, as distinct, but not discrete, categories, while also offering deep, critical, close readings of her chosen texts. One such text is Lorraine Hansberry’s unproduced screenplay The Drinking Gourd, which according to McCormick, exemplifies the contemporary black playwright’s engagement with slavery (and by extension, fugitivity) in her dramas. Using Hansberry’s political activities and the revolutionary backdrop of the 1950s as an anchor, McCormick highlights how The Drinking Gourd challenges the historical record of slavery in its representation of black people, and encourages contemporary viewers to “steal away” from it. Specifically, McCormick points to Hansberry’s challenge to mainstream and archival representations of enslaved folks, shifting the perspective away from the slave masters to that of the enslaved. Another is Slave Ship by Amiri Baraka—meant to demonstrate the practice of revolutionary fugitivity—which is on the run from narrative cohesion and employs jagged, inchoate, and incomprehensible affective registers to imbue black subjects with the power “to dictate the terms of their mourning of slavery and collectively envision a potential independence” (32).

Turning to the second chapter, “Fugitive Acts,” McCormick focuses on August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean and its narrative and performative engagement with fugitivity. Though she does not explicitly name it as so, one might categorize Wilson’s work as occupying the space of revolutionary fugitivity. Concretizing her theory of “fugitive acts,” McCormick investigates Wilson’s work as “radical mourning” and puts it in conversation with black self-determination, black citizenship, and the project of America. In particular, Gem of the Ocean deploys bones as a metaphor, illustrated through Wilson’s imagining of the City of Bones as a way to articulate the gravity of black death and the black dead and create a space for mourning. Marronage, McCormick argues, undergirds Gem’s dramaturgical construction by staging a “theory of freedom” (60) that “refuses objectification of black bodies and forces audiences to see those brutalized as subjects” (75). Thus, McCormick contends August Wilson’s drama takes seriously the structural violence of anti-Blackness while avoiding characterizing his characters as completely incapacitated by it.

Whiteness enters the frame in the third chapter of Staging Black Fugitivity as McCormick examines dramas by Lydia Diamond and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. In “Performing Escape,” McCormick looks to Harriet Jacobs: A Play and An Octoroon as emblematic of the efficacy of performing whiteness as a way for “black subjects to challenge confining racial constructions and ironically forward more expansive representations of blackness” (78). Here McCormick takes on the distorted history of blackness as represented by white people, looking to the entangled legacies of slavery, blackface minstrelsy, and black performance culture. McCormick discusses Diamond’s Harriet Jacobs: A Play, an adaptation of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon, a contemporary response to the 1859 play The Octoroon, and how the two plays utilize performance as a way to question history . Both playwrights experiment with theatrical form through the use of adaptation—that is, they signify on existing, canonized works of literature—in order to dialogue with, critique, and move beyond their source material. The dramas, then, stand alone as autonomous texts, escaping the narrative conscription to which they were previously confined. In particular, McCormick looks at Diamond’s choice to cast black performers as white characters as one that cleverly engages with intertextuality and what she refers to as “representational freedom” (98). The performances of whiteness in both dramas, then, expand black subjectivity and free it from its constricting figural frame.

In “Fugitive Intimacies,” McCormick provides a deep engagement with the work of Robert O’Hara and his plays, Insurrection: Holding History and Antebellum to conclude her exploration of black queer subjects and fugitivity. McCormick looks to the space of intimacy to theorize black queer people’s “social making” in direct defiance of “active attempts to render black subjects as socially dead” (116). Framing this act as radical, McCormick sees the black queer characters in these dramas as agentive, investing in their own aliveness and sexuality. But it is not only this optimistic orientation that is activated in this chapter as McCormick dialogues with queer theorists such as Jack Halberstam and José Muñoz to make room for the space of failure. This is done not to turn away from the queer worldmaking enacted within the plays, but rather as a way to account for the oppressive structures of heteronormativity and “idealized endings”(134), and to conceptualize a space for black queer fugitivity that reorders hegemonic logics. McCormick sutures together these myriad discussions in her epilogue through brief readings of Suzan-Lori Parks and Claudia Rankine and their twinned projects of staging “the aftermath of the unresolved emancipation” (141) and the ongoing contradictions of anti-Blackness, citizenship, and the self-determined black subject.

Staging Black Fugitivity is in deep conversation with a number of playwrights, but also with the intellectual traditions of, and within, black performance. McCormick impressively weaves together multiple disparate threads among literary genres, dramatic literature, and performance to offer a robust conversation about the varying strategies of black performance. Though McCormick provides many terms and descriptions of fugitivity, she carefully and skillfully defines them. This may seem at odds with the ontology of fugitivity as that which is liminal and eluding capture but McCormick’s clarity allows for the mobility of the terms as well as a demonstration of marrying theorization with analysis. The text is decidedly dramaturgical in nature, with each chapter beautifully in conversation with the next and profoundly entrenched in its specific historical backdrop. Scholars and practitioners of literature, performance studies, and black cultural studies will find Staging Black Fugitivity useful for McCormick’s insights on black theatre and performance and its continued “rehearsa[l] of freedom.” (146)

There appears to be a greater interest from contemporary black playwrights in staging dialogues around slavery and freedom on the theatrical stage. Most recently, Jeremy O. Harris’s controversial 2019 play, Slave Play, gained equal parts critical acclaim and critique, with the work itself earning a record-breaking twelve nominations at the 74th Tony Awards. But even beyond the space of theatre, fugitivity has gained resonance. Television shows such as WGN’s now-cancelled Underground and HBO shows Watchmen and Lovecraft Country; films like Antebellum and Harriet; and even Janelle Monae’s 2018 emotion picture, Dirty Computer stage their own versions of fugitivity as theorized by McCormick. Thus, what makes Staging Black Fugitivity a relevant text for our times is that McCormick’s theories of fugitivity can help us both engage black theatre and performance as well as travel to other cultural terrains, moving us ever closer to liberation.

Jordan Ealey is a doctoral student in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. Areas of research include black theatre and performance; black feminist theories and praxis; musical theatre history; popular music; and black girlhood studies. Jordan’s work has been published in The Black Scholar, Theatre Journal, and Girlhood Studies (forthcoming).