Review by Anne Schobelock, Washington State University

Publisher: University of Illinois Press, 2021

Length: 272 pages

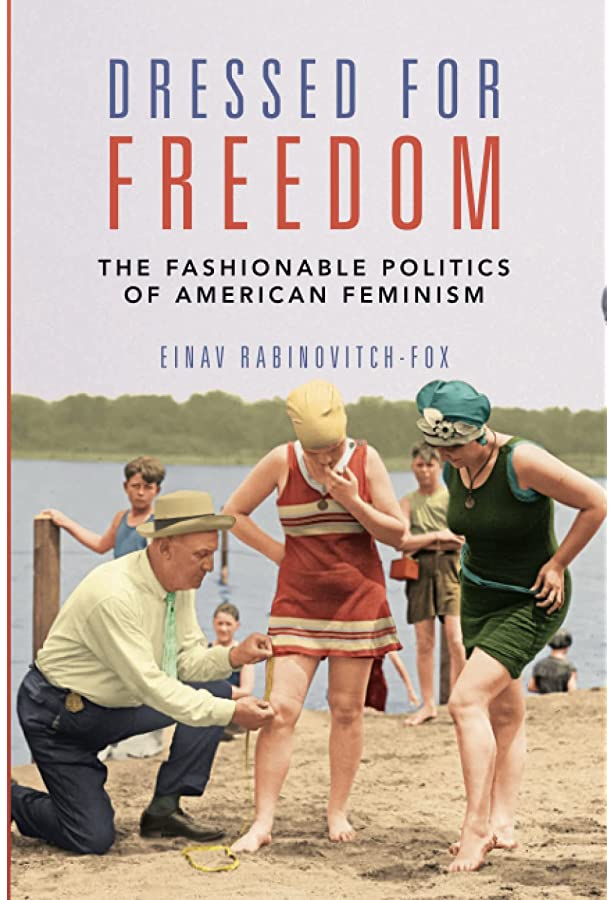

This fascinating and timely work will have you think twice about the clothes you put on every day. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox asks readers to take another look at twentieth-century fashion – this time, with a feminist lens. Throughout the twentieth century, she argues, women used fashion to express their politics and to influence mainstream consciousness. Dressed for Freedom examines the meanings that women gave to their style, and how they mobilized style to challenge gender, class, and race conceptions of femininity. Rabinovitch-Fox looks at both the symbolic power of fashion and the physical design of clothing that shaped women’s movement within space. Moving away from the framework of feminist waves to “highlight the continuities behind women’s sartorial practices to express feminist ideas and identities,” the work maps a continuous thread of feminism throughout the twentieth century (17). Her sources are rich and varied: periodicals such as the New York Tribune, Washington Post, Ladies Journal, Women’s Daily Wear; public and private writings of feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and visual/material evidence of illustrations, sewing patterns, and museum collections. The work examines the years 1890-1980, tracing five time periods, each shaped by unique fashion trends.

Rabinovitch-Fox opens the work with a discussion of the Gibson Girl, whose white shirtwaist came to represent the independence, athleticism, and education of the New Woman. The style of shirtwaist and shorter bicycle skirt removed the restrictions of Victorian Era fashion. Although the Gibson Girl was advertised as a white woman, the style was also donned by immigrants and African American women as a method of social inclusion. From the era of the Gibson Girl, Rabinovitch-Fox moves on to Greenwich Village and Suffragist women in the 1910s, arguing that, although their goals overlapped, their fashions differed. Greenwich Village women used Japanese kimono fashion to emphasize their unique style and to blur gender lines. At the same time, Suffragists used fashion to gain public support of their cause by pushing against ideas of the masculine looking feminist. For suffragists, clothing was a united effort that demonstrated a fashionable active lifestyle.

In the second half of the work, Rabinovitch-Fox adds a fresh and intersectional analysis to well-known styles. She brings the fashion of Black women to the fore and argues that the consumer culture and flapper style of the 1920s was used by women to push feminism further into the public mainstream. Black flappers adopted a short dress style as part of the growing youth culture of inclusion. For working-class Black women, the flapper style challenged not only gender structures, but racial ones. From flappers she shifts to popular styles of the 1930s through the 1950s when “Sportswear” acted as a continuous thread of feminist discourse and dress. By looking at women fashion designers like Claire McCardell, Rabinovitch-Fox demonstrates how sportswear served as a form of mobility and freedom despite the cultural backlash of the 1950s. She closes the work with a discussion of fashion and late-twentieth century feminism. Fashion of the New Left included both mini-skirts and pants; and often worked to push against the “anti-fashionable feminism” trope. However, she notes, there was disagreement between radical feminists (sometimes associated with lesbian feminist) and national organization leaders like Gloria Steinem and Betty Freidan. It is her rich discussion of such disagreements, which, for some readers, will serve as “page turners.”

Dressed for Freedom offers fresh and layered analysis of women’s fashion. The opening of each chapter provides context for how women performed and were perceived in the public world, this includes mention of national and global events such as World Wars I and II. She is able to do this without detracting from the agency of the women, whose choices and actions remain centered throughout her work. Rabinovitch-Fox craftly demonstrates how women used clothing as both a practical means to operate in public, and to express feminist ideals. Her treatment of Black flappers demonstrates the need for more intersectional analysis of both women’s fashion and feminist movements. This reader hopes Rabinovitch-Fox’s work will inspire similar trends in other scholars of both feminism and fashion. While Dressed for Freedom’s emphasis of East Coast publications and organizations that operated out of New York is understandable — New York is/was the fashion headquarters of the U.S.— this did, at times, telescope the worlds of women’s fashion and of women’s feminism. Mexican, Chinese, and Japanese women make a brief appearance in 1920s, and then disappear. That said, the work is accessible and carefully crafted. Its gendered and political analysis of women’s fashion will prove useful for scholars of gender, politics, as well as fashion. The work provides a comprehensive overview of both the popular trends throughout the twentieth century and a thoughtful analysis on how women created and mobilized fashion trends for their own political goals. The work, although not fully removed from the constraints of the feminist waves framework, serves as an example of how scholars can think about women within larger, more layered and perhaps more useful frameworks. Feminism was part of everyday life, and fashion was a vehicle for moving both liberal and radical feminism into the U.S. mainstream.

Anne Schobelock is a graduate student in the department of history at Washington State University with an interest in twentieth century women and gender history, fashion history, and feminism.