Review by Eylül Yel

Publisher: Stanford University Press , 2020

Length: 304 pages

Beauty Diplomacy takes us inside the world of Nigerian beauty contests to see how they are transformed into contested vehicles for promoting complex ideas about gender and power, ethnicity and belonging, and a rapidly changing articulation of Nigerian nationhood. Drawing on four case studies of beauty pageants, this book examines how Nigeria's changing position in the global political economy and existing cultural tensions inform varied forms of embodied nationalism, where contestants are expected to integrate recognizable elements of Nigerian cultural identity while also conveying a narrative of a newly-emerging, globally-relevant Nigeria.

It is easy to dismiss beauty pageants as sexist or inconsequential. After all, many pageants continue to make judgments and enforce rules based on women’s body measurements, age, and marital status. Oluwakemi M. Balogun’s Beauty Diplomacy: Embodying an Emerging Nation, however, examines beauty pageants in their full complexity by recognizing aspects of pageantry that some scholars deem troublesome while simultaneously honing-in on the industry’s role in diplomacy, nationalism, and international politics. Set in Nigeria, the fastest-growing economy in Africa, beauty queens emerge as role models of the nation. Tracking the effects of economic globalization, cultural politics, and gendered power, while remaining attuned to contestants’ interpretations of events, Balogun skillfully illuminates how “beauty diplomacy” shapes Nigeria’s stance in the global economy through the strategic position of women who partake in beauty pageants.

In 2001, Agbani Darego of Nigeria was the first Black African to win the Miss World pageant. The achievement initiated a series of events that set the stage for the study. Balogun’s personal interest burgeoned during a visit to Nigeria where she encountered countless advertisements promoting one of over 1,000 beauty pageants held annually in the country. To carry out the project, starting in 2009, Balogun spent eleven months in Nigeria whilst working behind-the-scenes as an unpaid intern for The Most Beautiful Girl in Nigeria (MBGN) and as a chaperone for Queen Nigeria where she interviewed owners, organizers, producers, corporate sponsors, contestants, judges, and critics. Outside of the pageant settings, Balogun interviewed makeup artists, journalists, production crew, photographers, fashion designers, and fans.

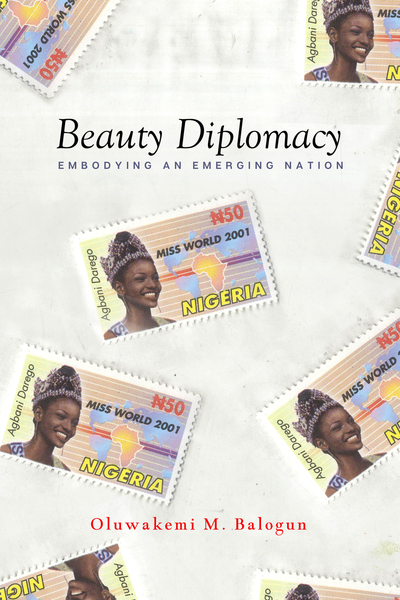

Balogun grounds Beauty Diplomacy in the context of Nigeria’s strained reputation in the global economy. Most people are familiar with Nigerian-based email phishing scams or similar business-investment schemes. Stories linking fraud to Nigeria continually circulate in international media, tarnishing its character and standing. When the United States issued travel advisories from 1993 to 2000, cautioning passengers about criminal activity in Nigeria, it resulted in declining tourism revenue, and thus put a dent in the economy. Agbani Darego’s 2001 Miss World victory allowed officials to mend the nation’s tainted reputation and establish itself as an important member of the international community, a process Balogun describes as “redemptive politics” (9). Various organizations parlayed her win to advance a new image of the nation. For instance, the Nigerian Tourism Development Corporation (NTDC) invited Darego to multiple exhibits in Europe and the United States that featured large photographs of her wearing the Miss World crown along with images of prominent tourist locations in Nigeria, while the Nigerian Postal Service (NIPOST) issued stamps commemorating her victory. As these examples illustrate, women’s bodies not only “symbolically stand-in for the nation,” but elevate its profile and materially integrate it “into the global economy” (13).

Beauty pageants served as focal points for restoring national credibility, helping boost Nigeria’s transition from developing to developed country status. They also helped forge a sense of nationalism. In a country of over 250 ethnic groups, many Nigerians identify with an ethnic or regional identity rather than a national one (39). Nevertheless, beauty queens collectively engage in embodied work to represent a unified sense of Nigeria in an effort to improve Nigeria’s global standing (40). Balogun contextualizes these dynamics using an “African rising realist” approach that acknowledges the opportunities that beauty pageants create for emerging nations while noting the need for additional infrastructural changes before significant demographic and economic advancement can be achieved. Latent instability continues to characterize the region; political uprisings, chronic disease, and famine are still a part of reality despite growing pride for Nigerian music and Nollywood films (5).

One of the book’s many strengths is the integration of Nigeria’s colonial and postcolonial history in relation to the structure of pageants. Colonial conditions created vast ethnic and religious diversity within the nation. Culture influences how pageants operate. Some pageants, such as The Most Beautiful Girl in Nigeria (MBGN), take a cosmopolitan-nationalism approach by focusing on cosmopolitan elements of Nigeria to represent the nation as urbane (63), while others, such as Queen Nigeria, appeal to cultural-nationalism by taking a “unity in diversity” approach (66). Despite their distinct approaches, both pageants position their contestants as role models and ambassadors who will restore Nigeria’s image through “embodied” work. Ideas about the nation are created and challenged by centering women’s bodies as stand-ins for Nigeria through beauty pageants (19).

Similar to sporting events such as the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup, beauty pageants garner international attention. Yet, they are not treated as equally indispensable. Balogun’s comparison of Nigeria’s approach to Miss World and the FIFA U-17 World Cup demonstrates how diplomacy discourses are often linked to masculinity (19). In 2009, Nigeria successfully hosted FIFA U-17 World Cup, in spite of threats from an armed militant group. The government offered the organization amnesty in exchange for their weapons and the conflict quickly ended. In contrast, plans to host Miss World 2002 resulted in a public relations disaster when the event was moved to London two weeks prior to the scheduled date due to unrest stemming from the mistreatment of women under sharia law. Unlike the strategic response to the FIFA World Cup conflict, growing concerns around safety led Nigeria to prioritize protecting the contestants, rather than navigating the conflict.

Balogun’s study illustrates how beauty pageants function differently in developing countries. In addition to boosting a nation’s international reputation and creating a unified sense of nationalism, pageants create business opportunities. In 2014, Nigeria became the largest economy in Africa, surpassing South Africa. And, while oil and gas dominated a large portion of that growth, the service sector grew exponentially as a result of new businesses operated by former beauty queens. Women’s economic contributions, however, remained less recognized by officials, and thus less valued, because of gendered expectations that are associated with international role models.

Most notably, Balogun’s study offers a new perspective to discussions surrounding “embodied nationalism”. Although a growing body of research has been done on militarized masculinity to demonstrate how ideas about a nation are created through gendered bodies, Balogun specifically focuses on how beauty diplomacy as a form of embodied nationalist strategy is used to navigate national conflict (42). Beauty Diplomacy similarly makes contributions to the literature around “gendered diplomacy” where women are positioned to serve as political or cultural ambassadors by offering a comparison between the beauty pageant contestants and the influence of first ladies in cultural representation. Balogun’s study on beauty pageants can be applied to other cultural and political events to measure the impact they have on crisis management and a nation’s overall global standing (234).

In closing, Beauty Diplomacy makes significant contributions to research on globalization, nationalism, and gender. Much of the Western feminist criticism around beauty pageants continue to deem them oppressive. However, there is a group of scholars who argue that beauty pageants can serve as platforms in which cultural diversity is celebrated where numerous opportunities are made available to women. Balogun’s work connects these views by recognizing the hierarchies of power in pageant settings without classifying them exploitative or empowering, but rather focuses on beauty pageants as sites where ideas about power and difference are revealed (24). Questions about power continue to circulate as developing countries put a heavy emphasis on beauty pageants for growth and recognition, while ultimately countries that are already in a position of power seem to benefit the most from them (231). Balogun’s study gives the readers an insight into the polarizing nature of beauty pageants. As pageants continue to grow in popularity in many countries across the world, so does the criticism against them. Although pageants may no longer solely focus on physical attributes, and contestants are evaluated on civic engagement, women are still expected to remain respectable, pure, and desirable. Traditional gender norms remain enforced even when structural changes are seemingly in place to benefit women. Elegantly written and clearly presented, Beauty Diplomacy would be a welcome addition for undergraduate classes on gender, development, and globalization. Additionally, Balogun’s thorough analysis, grounded in transnational and postcolonial feminist theory, would make the book a fascinating read for graduate seminars on the body, femininities, the nation, and culture.

Eylül Yel is a Master of Arts candidate in Communication at Washington State University. Her research interests include intercultural communication, gender and mass media