Review by Candice Crutchfield, The Ohio State University

Publisher: University of California Press, 2022

Length: 342 pages

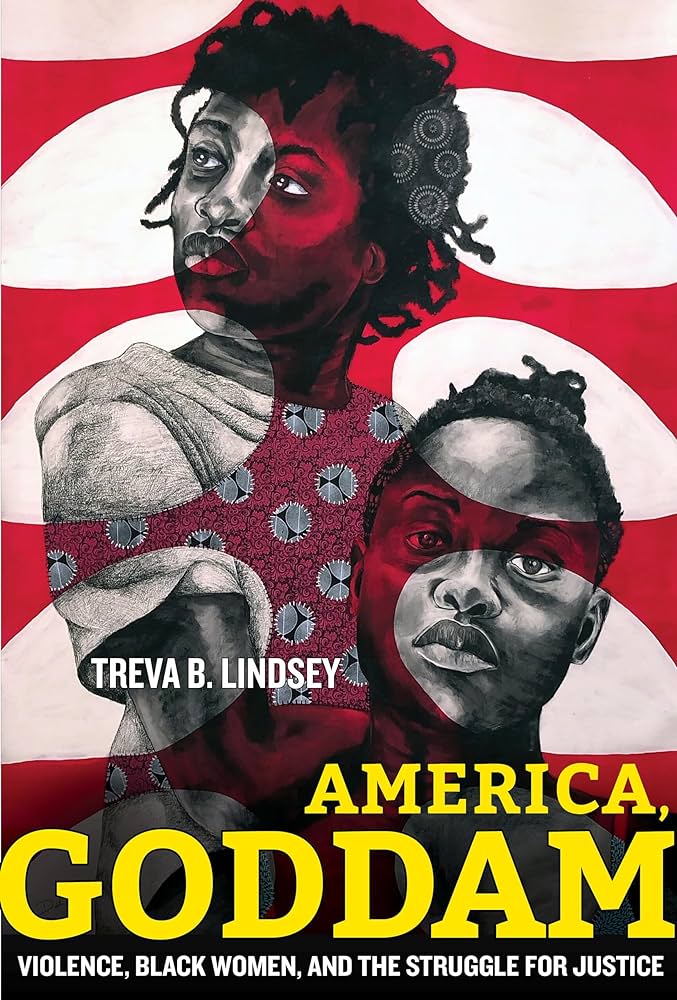

Treva B. Lindsey’s America, Goddam: Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for Justice provides an in-depth examination of the lived experiences of Black women throughout the history of the United States. Exploring theories of power and inequality, anti-Blackness, misogynoir, and racial capitalism, Lindsey highlights the ways in which Black women not only face disproportionate vulnerabilities and increased risk of violence but also, how such narratives are often othered in discussions of resistance, resilience, and struggles for Black liberation. Drawing from historical analyses and personal anecdotes, Lindsey doesn’t shy away from what some may deem uncomfortable conversations of inter-communal violence, punishment, sexuality, and oppression, rather, she makes visible the often overlooked, day-to-day experiences of Black women in America.

A professor, historian, and expert on Black feminisms, Lindsey draws inspiration for the title and opening of the text from Nina Simone’s, “Mississippi Goddam,” a protest piece, composed to capture the unjust murders and anti-Black violence during the 1960s freedom struggles. Beyond Simone’s lyrics, Lindsey anchors many of the chapters with messages and quotes from Black women artists, activists, and abolitionists, again, exploring the Black woman as one occupying a particularly unique status. While each chapter can stand alone, they come together to form a beautiful mosaic, exploring the complexities of Black girlhood and womanhood within U.S. contexts. As such, Lindsey’s work is perhaps best discussed when organized into three distinct groups: (1) Black women’s encounters with violence and punishment (2) the experience of unlivable living, and (3) popular culture, power, and resistance.

Lindsey uses the opening chapter of the text to provide readers with a history of the policing of Black personhood, situating the phrase “violent policing” as one of redundancy (p. 33). She continues, drawing upon individual case studies of Black women Eula Love, Sandra Bland, Deborah Danner, and others who have experienced considerable violence from police, social workers, and other law enforcement entities. From this, emerges elements of the criminalization of Blackness, but also that of disability, houselessness, and poverty. Chapter 2 extends conversations of state-sanctioned violence to include that rendered by the larger carceral system. The author makes clear a discussion of intersectionality, Black womanhood, and the distinct experiences of Black trans women as those who remain, “particularly vulnerable to criminalization” (p. 95). Drawing again from personal experiences and those of countless Black women both named and unnamed, Lindsey situates the inherent intersections between policing, punishment, and sexual violence for which few are truly held accountable. Chapter 3 can be read as a call for action and acknowledgment that many harms inflicted upon Black women and girls are often the result of misogynoir, patriarchy, queerphobia, and ableism within Black communities (p. 123). The chapter ends with a clear message: violence against Black women and girls, “manifests in multiple forms, some not as easily identified as gender or sexual violence at the hands of loved ones or brutality at the hands of police” (p. 149).

Much of chapters 4 and 5 contend with Judith Butler’s concept of unlivable lives. To Lindsey, anti-Blackness, economic deprivation, and medical violence create multi-system harms that disproportionately impact the lives of Black women. From histories of gynecological experimentation on enslaved Black women and more recent skyrocketing maternal mortality rates to environmental racism and negative discourse surrounding those living in poverty, American societies render an instance of ‘unlivable living,’ forcing Black women into a “death-bound condition” otherwise seen as a form of state-sanctioned violence.

Discussed within the context of personal experiences, chapter 6 explores the difficulty of maintaining resilience in the face of misogynoir and the politics of disposability. Drawing from Patricia Hill Collins, Lindsey highlights the controlling images of Black womanhood, arguing that despite efforts to demean, criticize, and stereotype, a successful movement requires the removal of shame and open acceptance, “the rejection of the status quo including stereotypes, tropes, and controlling images is an uphill battle in Black women and girls’ struggle for justice” (p. 255). Chapter 7 continues this messaging, highlighting the concentrated effort to #SAYHERNAME and the many ways in which Black women have historically been at the forefront of the ongoing collective struggles for justice.

Following the concluding chapter, Lindsey uses the epilogue to openly compose a “letter to Ma’Khia Bryant,” a 16-year-old Black teen who was murdered in Columbus, OH, within minutes of a police officer arriving on the scene. Recounting the last moments of a young life taken too soon, Lindsey highlights the multiple system failures that, rather than rendering compassion and care, showcased the system’s complicity in promoting a racialized and gendered schema rooted in violence and white supremacy. Ma’Khia’s story draws connections to earlier chapters on punishment and serves as a continued reminder of the margins on which Black women and girls are often relegated. While considerable attention is rightfully paid to the trauma and risks associated with Black womanhood, Lindsey’s overall work still reads as a love letter to Black women and girls. I, myself, a Black woman, could not help but feel seen within the pages and chapters of the text, often closing the book with the affirmation that my experiences and desires are shared with a much greater community.

“Getting free is still our north star,” concludes Lindsey, after uplifting the names of freedom fighters and providing a framework in which we can envision a more just world beyond ‘unlivability’ and survival (p. 234). While it may be difficult to conceptualize change within our lifetime, the truth of Lindsey’s conclusion is that freedom won’t come overnight, and it most definitely doesn’t come without action. By centering the lived experiences of Black women and girls, Lindsey makes clear the importance of resistance efforts in the face of brutality and invites everyone to participate in collective responses to it. America, Goddam is a brilliantly written “must-read” providing readers with a critical lens to understand the unique experiences of Blackness within the United States. Ultimately, it operates as an essential text with important literary contributions both within and beyond academic scholarship.

Candice Crutchfield is a doctoral student in Sociology at The Ohio State University. As a scholar of critical criminology and sociology, her teaching and research interests include the collateral consequences of incarceration, the commodification of punishment, Black feminist perspectives, and abolition.