Review by Shelli Rottschafer, Aquinas College

Publisher: Torrey House Press, 2021

Length: 350 pages

For those new to Kathryn Wilder’s nature-based creative nonfiction, she draws from her life, and how her decisions have affected not only her, but her family and the advocacy she lives as well. Her work has been cited in Best American Essays and nominated for the PEN America Literary Award and Pushcart Prize. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications such as High Desert Journal, River Teeth, and Sierra. Wilder graduated from the low-residency MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. She lives among mustangs in southwestern Colorado, where she ranches with her family in the Dolores River watershed. This place and others dear to her, as well as the traumas and joys experienced in those lands, inspired the writing of her memoir.

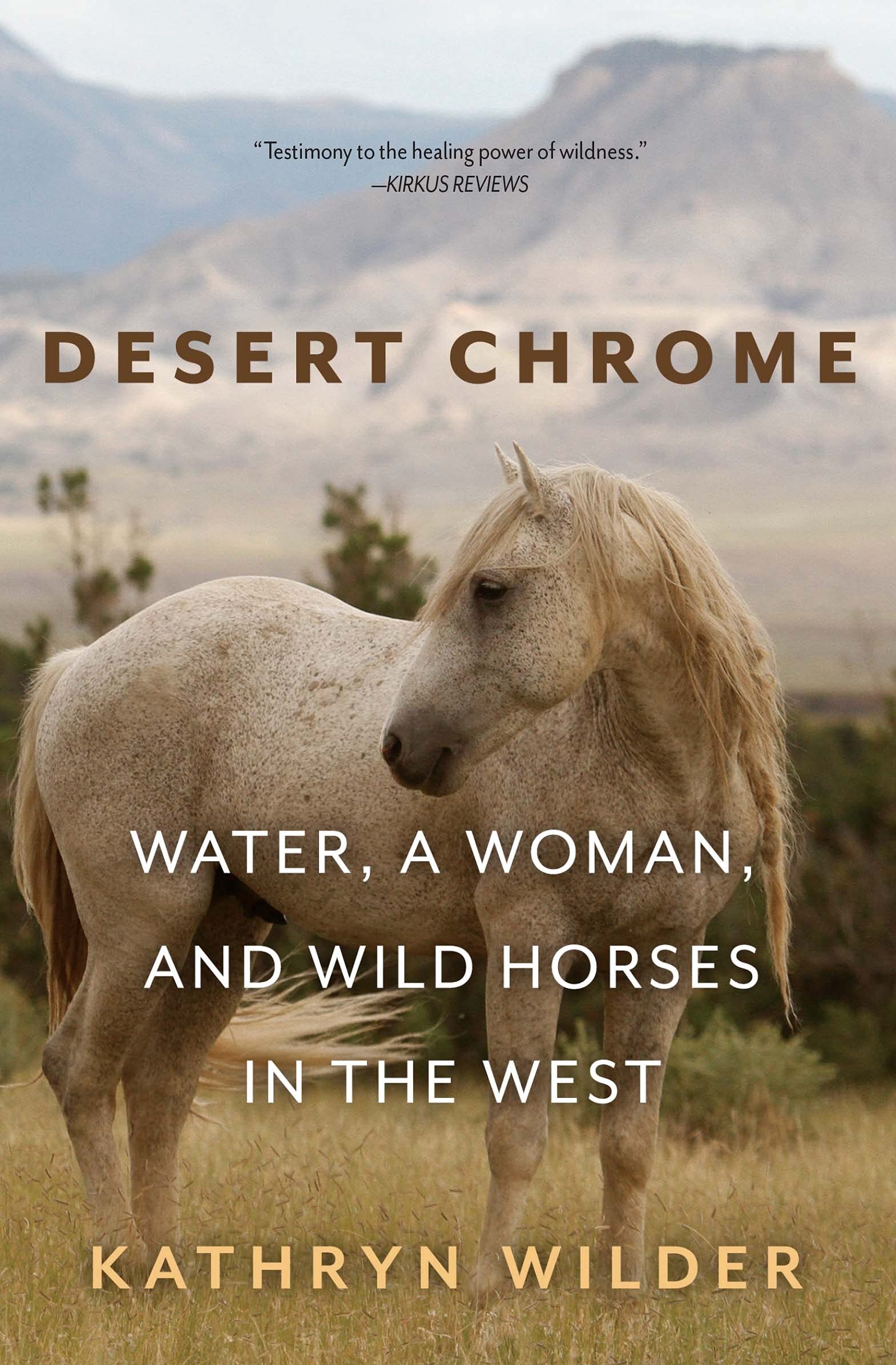

Wilder’s Desert Chrome: Water, A Woman, and Wild Horses in the West traverses western frontiers from the Colorado Plateau to her childhood origins within the California Northern Sierras, which recently blazed with the Dixie Fire. She leads us across the Pacific Ocean to Hawai‘ian Islands kissed by waves and saddles up against the Grand Canyon Rim in Arizona.

In her Prologue, “The Last Drink,” Wilder is reminded of her foibles when she backsteps into a prairie dog hole, falls ass-over-end on a stone slab, or nearly missteps down a piñón-lined, single-track mountain trail. These mishaps play the chiding statement of her eldest son Ken in her mind: “Jeez Mom…. Just don’t walk backward” (4). This metaphor is not lost on Wilder; she realizes that, “stepping back may no longer be appropriate” (4).

Throughout her life, leaving, the preparation for a departure, or the temporary has been enough. Until it wasn’t. She admits, “Whether leaving is a skill or a malady, I know how to do it. It’s staying that’s a mystery” (13). Yet now, finally established in Dolores, Colorado after years on the move, she is taking William Kittredege’s advice to stay, because by staying, one makes a choice to fix where one is rather than leaving in hopes of the elusive greener pasture.

Wilder’s memoir leads her reader, sometimes at a gallop, other times at a canter or trot, but continually she choses to walk forward instead of taking that step backward into addiction due to trauma caused by childhood molestation, divorce, and family separation. Wilder posts onward and takes the challenge her son voices, to no longer step backward.

For many, Hawai‘i seems like living a dream within paradise where the place itself creates a space by, “doing what Hawai‘i does – creating, and in our case recreating, ‘ohana. Family” (57). Yet Wilder’s Maui seems to be a place of goodbyes. This is where she says goodbye to a lover of five years, goodbye to the fraught relationship with her biological father, goodbye to her han‘ai father who withered away from cancer, goodbye to the waves that carried her to recovery, that lofted her forward yet tempted to hold her back in their riptides. This beautiful paradise was not always heavenly for her but helped make Wilder who she is despite the pains.

California is the land where Wilder’s childhood haunts act as the kindling to flame. Perhaps these memories are well buried in its ashes; still Wilder felt heartache as the Dixie Fire raged. In its strength it consumed acreage, destroyed structures, and threatened to spark memories she had buried. In hindsight, Wilder contemplates the journey she has taken thus far: “I could see the rugged terrain behind me but not the landscape of my future…. In the past, drugs have given me motivation, direction…. I can’t do what I did when I was eighteen, nineteen, looking for someone else to be. I have to find who I already am” (59). The Dixie Fire as an analogy is fitting. Does the devastation scar or allow for a purging, a renewal?

Wilder continues to grapple with the why of her existence. She is constantly tested, her own mortality in her hands, as she views from afar the suicide of her best friend since childhood. Rebecca is her chosen sister, the one adopted into her family, the cherubic blond with mesmerizing blue eyes. A sister, in more ways that understood, as she too was an addict, using not heroin but prescription pills to ease her pain, los dolores.

Arizona and New Mexico mark Wilder’s years on and off in graduate school. These are the places where Wilder learns to write her way forward through the pain and the loneliness with only her rescue dog Cojo at her side. Who rescued whom? Wilder wonders aloud in her prose:

“We were only women waiting for a short time, but how many years have we, as women spent waiting? For the right man, for that man to call, for him to arrive at the door; waiting to conceive, for the birth to happen… Then waiting for things to get better… When one waits, is one not living?” (31).

As a woman now in her sixties, Wilder is no longer willing to wait or take a step backward. Like a friend advised: “This is your life. Now. You can just sit here waiting, getting older, or you can do something – it’s your choice” (46). Wilder’s choice is action, to write her way forward, finding the lessons through her pain. Her revelations on the page hope to impart some wisdoms that she has learned, so that others do not feel so acutely the pangs from burying their own addictions.

What Wilder slowly comes to understand is that the outside is her means of grounding. Pills, cocaine, heroin, alcohol no longer provide the calm. “I felt right there, right inside myself. If I had known anything about spirituality – of God – I might have understood that the ingredients of a place had answered prayers I didn’t know I made” (67). Finding her connection in nature is where she discovers balance, and this most cherished place becomes Dolores, Colorado.

The emergence of Colorado in Wilder’s life took a while for her to feel. But the beauty of its shimmer, the right north-northwest flow of the rivers, the red rock and the pine trees, all clutched her, “heart the way roots clasp canyon walls” (131). This is where Wilder’s loves for her extended family and wild mustangs blend into an advocacy and allow her to discover her querencia.

Querencia is a hybridized word. In Spanish it is derived from the verb querer, meaning to love, to want, to desire; and herencia, a noun meaning heritage and legacy. Like the first mustang she met, Patty, who, “as soon as she felt trapped … would turn her head against the bit and run to a safe corner of the field or buck or sidestep or head for low branches or into the willow thickets at the end of the pasture where snow became marsh in the spring” (36), Wilder has found her safe corner, the green pasture that is good on the other side of addiction: Dolores, Colorado. Although perhaps appropriately named after her pains, Dolores is the place where she finds her strength, her place to bear down, no longer needing flight but a position to fight for herself, her community, and for our other-than-human relatives: The Wild Mustangs of Disappointment Creek.

Wilder’s intended audience includes those readers who are drawn to similar locales: Greenville, California; Ha‘iku Maui, Hawai‘i; Flagstaff, Arizona; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Dolores, Colorado. Her heartaches written on the page are our connection to her placenames of querencia. Her advocacy teaches us to not backstep but to accept those challenges going forward, whether through our own writing for personal growth, or through voicing for those without an ability to do so. Her lessons learned, el dolor has taken her to a place to stay where she gains strength, for herself, her community, the water that is lifeblood, and the blood that runs through the four-legged veins of wild mustangs.

Wilder’s Desert Chrome has a similar power that other memoirs have had in feminist theorizing, in that she uses the personal – writing as a witness – to build the threads that run through her narrative and guides her advocacy on the land.

Shelli Rottschafer completed her doctorate from the University of New Mexico in 2005. Since 2006, Rottschafer has lived near Lake Michigan’s shoreline and within its deciduous hardwood forest. She teaches at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, MI as a Professor of Spanish. Her academic research includes Latinx, Chicanx, and Indigenous American Literatures as well as Eco-criticism and Nature Writing.