Review by Clara Montague, Grinnell College

Publisher: The New Press, 2023

Length: 352 pages

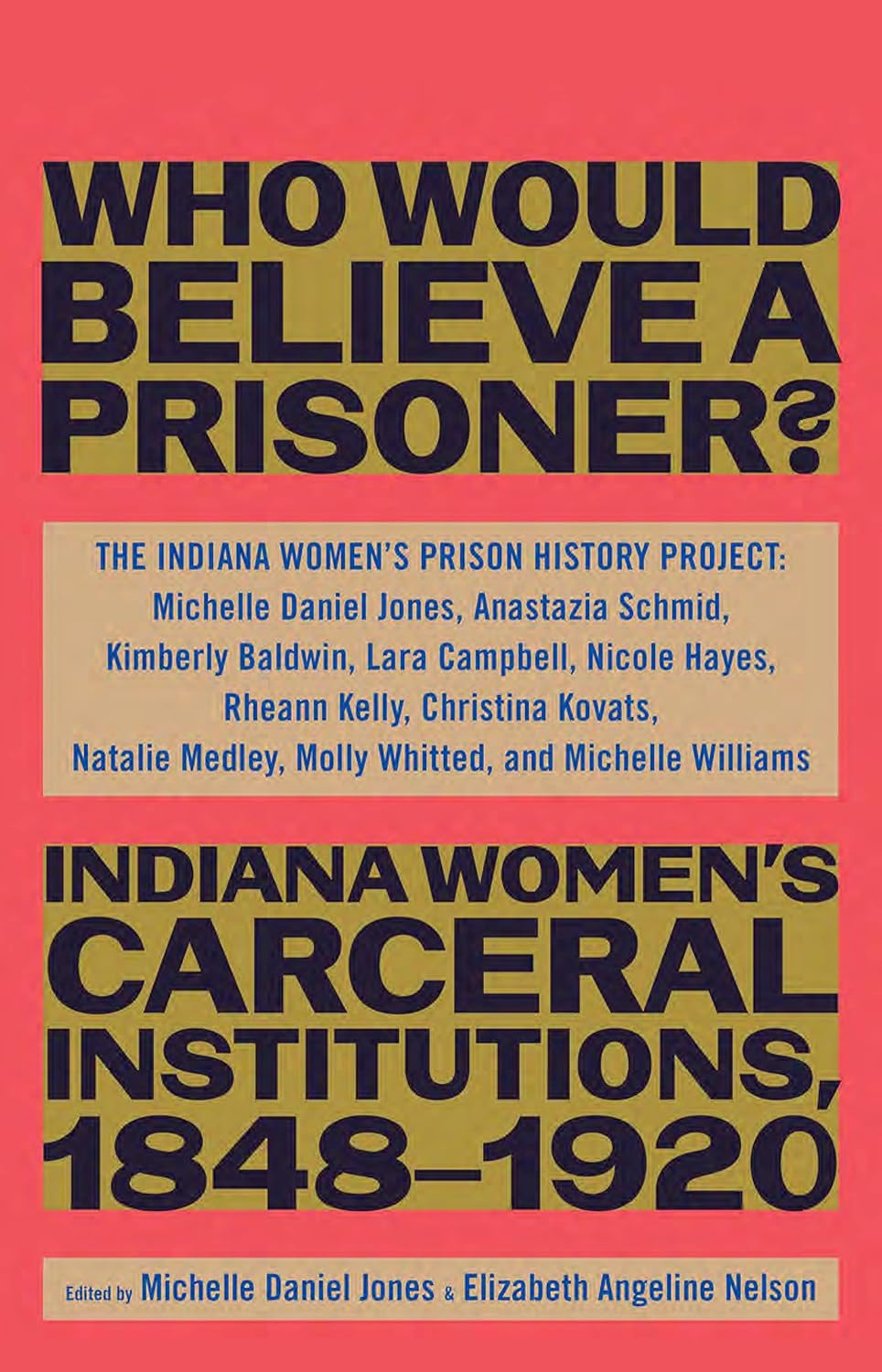

Before readers even open its front cover, Who Would Believe a Prisoner? poses a powerful epistemological question about how institutions function through the repression of marginalized voices. The title quotes Harrie Banka, whose 1871 exposé of systematic corruption and sexual abuse at Indiana’s Jeffersonville State Prison accelerated Reconstruction Era calls to establish separate reformatories for women. In this book, members of the Indiana Women’s Prison History Project renarrativize the first all-female carceral institution in the United States from the perspective of those who lived there, thus revealing how ostensibly “gender-responsive” prisons further entrench and legitimize state violence. As women have become the fastest-growing demographic of people incarcerated in the U.S., this collection advances our understanding of how the prison industrial complex evolved its tailored mechanisms of surveillance and domination as well as how these might be subverted through education and knowledge production grounded in lived experience.

In her preface, program founder Kelsey Kauffman describes the immense challenges associated with maintaining a college in prison program, not to mention facilitating original student research in a setting characterized by restricted access. Given this context, Michelle Daniel Jones’ standout methodology chapter employs the frameworks of epistemic justice and critical participatory action research to show how incarcerated people’s institutional expertise can generate new lines of inquiry based on what may be excluded from official records. The authors of Who Would Believe a Prisoner? define their standpoint as that of an “embodied observer” or “one who views the archive from the position of the captive, from the inside of their experience.” While these scholars continually struggled to validate their status as knowers, external “disqualification” also allowed the critical implications of their findings to fly under the radar and avoid censorship by the Indiana Department of Corrections.

This methodology of “chronological distancing” that nonetheless draws tacit parallels between past and present-day forms of oppression recurs throughout Who Would Believe a Prisoner? Its first section traces how expectations of white, middle-class Christian womanhood were foundational to the advent of gender-segregated carceral institutions. Jones along with Kim Baldwin, Molly Whitted, and Michelle Williams argue that the “cult of domesticity” reinforced a bifurcation between “fallen” women seen as victims of circumstance and true criminals whose race, disability, immigration status, or sexual impropriety located them beyond the reach of rehabilitation. Furthermore, these gendered logics structured the residential organization of prison life into pseudo-family “cottage” units where, under the auspices of a live-in matron, women were forced to enact their proper roles as housewives or maids.

Ironically, the work of governing this reformatory allowed women employees greater personal freedom—carving out a socially acceptable space for themselves not only to work outside the home but also to exercise political power. While single-sex prisons may have allowed a better quality of life than mixed institutions, the system’s expansion relied on criminalizing women’s sexuality, which as Baldwin explains, “created a vast group of people subject to immiseration in prison and therefore in need of uplift by the benevolent elite.” Providing historical context for current feminist debates around state surveillance, abolition, and child welfare, Who Would Believe a Prisoner? demonstrates how the professionalization of criminal justice and social services primarily benefitted women who already possessed relative privilege.

The book’s second section elaborates how institutions utilized the emerging medical fields of gynecology and psychiatry to demonize sex work, regulate reproduction, and legitimize medical abuse. Anastazia Schmid aptly compares the captivity of incarceration and enslavement, both of which designate certain bodies as “deviant and hence…disregarded and discredited by society, which in turn made them prime candidates for ‘reformation’ and experimental ‘treatments’ as forms of bodily control.” As Nicole Hayes argues, such practices fed into nineteenth century panics over prostitution and “white slavery” while conveniently obscuring the system’s own complicity with women’s sexual exploitation. Molly Whitted extends this analysis to address the eugenicist practice of incarcerating “feeble-minded” women solely for the purpose of restricting their reproductive capacity. These themes are dramatized in The Duchess of Stringtown, a one-act play that speculates whether the untimely death of infamous Indianapolis madam Johanna Kitchen may have been facilitated by local elites and prison officials seeking to bring the city’s vice district under their purview. While distinct from traditional historiography, this creative piece resurrects a story that might have otherwise gone untold. As Kitchen’s ghost declares at the end: “Someday my voice will sound from the grave. The truth of all this will indeed surface.”

The book’s final section emerged out of Michelle Daniel Jones’ stunning realization that, at least officially, no women were imprisoned for prostitution or other sex-related offenses during the first twenty-five years of gender-segregated incarceration in Indiana. This unlikely finding instigated new questions about the forcible confinement of “incorrigible” women in House of the Good Shepherd convents akin to Magdalene Laundries. Christina Kovats, Natalie Medley, Rheann Kelly, and Lara Campbell follow this thread to reveal the proliferation of private carceral institutions run by Catholic nuns, which often held marginalized women for indeterminate sentences regardless of their actual criminality. Though some commitments were voluntarily, dozens of similar “homes” operated across the United States, imprisoning women for sex work, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, poverty, and pregnancy outside of wedlock. These findings highlight how religion became part of the carceral apparatus, facilitating the misappropriation of public funds and enabling spiritual abuse against vulnerable people.

Written accessibly with a careful balance between locally specific and broadly applicable analysis, Who Would Believe a Prisoner? would be well-suited to classroom instruction, particularly in courses on women’s history or feminist research methods. It also offers valuable insights for practitioners who work with currently or formerly incarcerated people, whether in education, corrections, or social services. As a piece of scholarship, the collection follows in the tradition of scholar-activists like Angela Davis, who use their own experiences to theorize the prison industrial complex in ways that invite radical reimagining. As coeditor Elizabeth Nelson concludes: “The writing of this book was at heart a clandestine and subversive operation; in the acts of researching, thinking, and writing, the authors claimed moments of fugitivity that are part of the long game of liberation. This is a book that was created in a prison, but it is not of it.”

Clara Montague is a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies at Grinnell College, where she also teaches with the Liberal Arts in Prison Program. Her scholarly interests include transnational feminist movements, digital cartography, and art activism. Clara earned her PhD from the Harriet Tubman Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Maryland.