Review by Jordyn H. May, Saint Paul College & Chippewa Valley Technical College

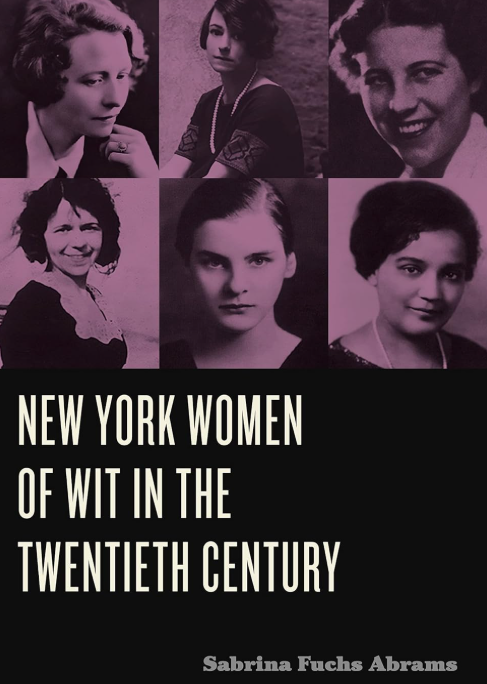

Publisher: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024

Length: 244 pages

Are women funny? Sabrina Fuchs Abrams, professor of English at the State University of New York, Empire State, and author of New York Women of Wit in the Twentieth Century, asserts not only are women funny, but women humorists in the interwar period “used satire, irony, and wit as an indirect form of social protest” (p. 1). Examining the works of six female humorists, Abrams illustrates how women interrogated traditional gender norms while addressing “larger question[s] of political and social reform,” breaking boundaries for women in humor today (p. 1). Focused particularly on the genre of satire, which Abrams notes is usually “written by an outsider,” the book investigates how humor “offers women and other marginalized groups an ideal way to voice their social protest through the socially acceptable form of laughter” (p. 2).

Abrams begins by surveying the literature and theories of humor, the descriptions of which are immensely helpful to understand the uniqueness and complexity of women’s humor. Each subsequent chapter reads as a standalone essay, connected through topic and basic argumentation, and loosely organized chronologically based on each woman’s most active writing years. The six humorists Abrams examines satirized male intellectual circles, bohemia, and class. To do so, they engaged with gendered hierarchies of power and women’s limited opportunities. Writing under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd, poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay critiqued the destructiveness of the patriarchal gender hierarchy.

Similarly, poet and writer Dorothy Parker challenged traditional gender norms in her satire. Parker used monologues depicting social scenarios such as a boring dinner companion, a phone call, or a dance to highlight the limitations of these female characters and their feelings of self-doubt as women attempted to be their authentic selves while also fitting into social expectations. Alternatively, novelist Mary McCarthy, a member of the Partisan Review in the 1930s and 1940s, believed satire to be an act of revenge against people in power. In her novel, The Group (1963), she satirizes the 1933 Vassar graduates to illustrate women’s limited opportunities and their failure to realize their personal potential. For example, the character Kay Strong is the first to marry, but also the first to divorce, losing her job and her home. She then dies tragically by accidentally falling out of a window. Like McCarthy, novelist and screenwriter Dawn Powell used satire to release anger in a way to cope with her own suffering and larger issues of social injustice. For Powell, satire was a way to expose the faults of the people in power, using laughter to create a community among those at the bottom. Unlike other humorists, her writing crossed class lines, satirizing the rich, the middle class, and the poor.

For writer and screenwriter Tess Slesinger, her Jewish identity and family dynamics influenced her satire. Slesinger became one of only two women associated with the Menorah Journal group, a secular, leftist Jewish magazine, and her 1934 novel, The Unpossessed, satirized this group of New York intellectuals. As Abrams argues, Slesinger’s discussion of controversial topics made her more overtly feminist as she fused the personal and the political, “anticipat[ing] more contemporary modes of feminism moving beyond a single definition of womanhood” (p. 99). Stressing the intersection of gender and race to promote social change, editor and educator Jessie Redmon Fauset explored the experiences of African American women during the Harlem Renaissance by using irony and satire to challenge the usual standards of the marriage and passing plots in her 1928 novel Plum Bun. Focused on two sisters who move to New York City, Angela, who passes as white, moves to Greenwich Village, and believes marrying a wealthy white man would provide her with happiness. After he abandons her, Angela comes to understand the importance of family and community as she sees her sister living a contented life in Harlem. By the end of the novel, both women are married and pursuing their own careers.

Abrams’ lack of critical engagement with sexuality, especially homosexuality, is apparent in her exploration of female bohemian and intellectual life in Greenwich Village. Free love and lesbianism feature in several of the satires examined, but Abrams fails to investigate further how the emerging concept of homosexuality as an identity could have shaped these women’s writings. Readers would benefit immensely from studying New York Women of Wit and Lillian Faderman’s Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers in tandem. Curiously absent from the former text’s citations, the latter examines the emergence of a distinctly lesbian identity and includes a deep exploration of Greenwich Village and Harlem during the same period.

Nevertheless, Abrams’ close reading clearly demonstrates how these women used humor to protest the social injustices they saw and experienced. Each woman pointed out the continued constraints of traditional gender roles despite women’s increasing sexual, political, and personal freedom embodied by the New Woman and the flapper. The inclusion of each humorist’s own words, either from interviews or diaries, supports her argument that these women purposefully used humor to engage in social protest. Abrams deftly interweaves criticism from contemporaneous critics to illustrate the reception of these women’s works.

This book brings new light to the intersectionality of race, class, and gender and how women recognized and protested the inequalities these constructions created in the early twentieth century. Scholars interested in women’s history, women’s studies, New York history, American history, and humor studies will be very interested and find much to discuss. Since each chapter can be read on its own, this book would also prove a valuable teaching tool in advanced undergraduate and graduate courses as students would no doubt find much to relate to. Positioning her study as an insight into feminist humorists today, Abrams effectively shows how women engage with humor to navigate and illuminate intersectional struggles with disability, discrimination, and gendered hierarchies of power to build community among all women.

Jordyn H. May is an adjunct professor at Saint Paul College and Chippewa Valley Technical College in the Twin Cities area in Minnesota. Her primary research interests are woman suffrage and women’s political culture in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. She holds a PhD in modern history from Fordham University.