Review by Codee Scott, Texas Christian University

Publisher: New York University Press, 2022

Length: 437 pages

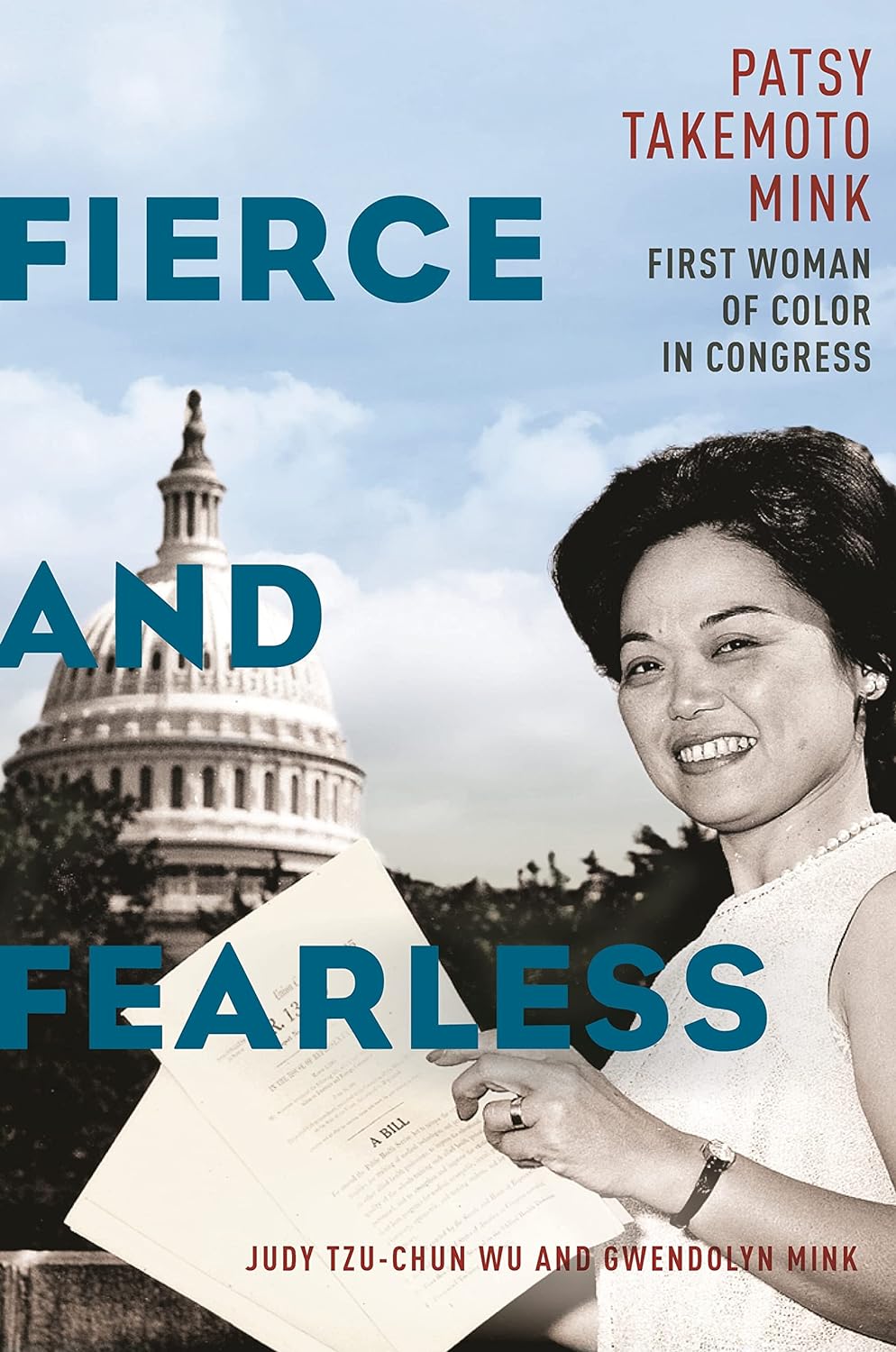

The 118th Congress contains a record number of women. In 2023, The House has a record-number of female representatives at 128, and the 25 female Senators is tied with the 116th Congress for its record. In total, Congress is currently comprised of 133 people of color, of whom 63 are women of color. To date, there have been 106 women of color to serve in Congress. The very first congresswoman of color was elected in 1964, nearly sixty years ago. That congresswoman, Patsy Takemoto Mink, has not been the subject of a biography until now.

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu and Gwendolyn Mink (Patsy Mink’s daughter) bring Mink’s life and career front and center, placing their work squarely within the historiography of women’s history, civil rights history, and environmental history while recounting Mink’s legislative achievements and goals, primarily using a feminist lens of analysis. The work argues that, serving as a bridge between legislation and grassroots feminist activism, Patsy Mink demonstrates that “the so-called liberal feminists . . . were not all white women who cared only about the middle class” (5). In essence, Mink was an intersectional feminist who fought for women and people of color, not just middle-class white women. Each chapter opens with Gwendolyn Mink’s personal vignettes about her mother’s life and career. Wu writes the bulk of the book, providing context and analysis for Mink’s opening vignette. This method of co-authorship provides the reader with both a sense of who Mink was as a person and the context for her legislative choices.

The book is divided into four parts, organized chronologically as befits a biography. The first section covers Mink’s life prior to her 1964 election to the US House of Representatives, including her family’s background, the history of Asian immigrants into Hawaii and their work in Hawaiian plantations, Mink’s schooling, and her early political career, in which the local media subjected her subjected to sexism and orientalism. Mink strongly believed in the principles of citizenship and the responsibility of the government to protect and provide for its citizens. The second section covers Mink’s first foray into Congress, divided into three chapters thematically covering Mink’s early opposition to the Vietnam War, creating and sponsoring feminist legislation (including the passage of Title IX and preventing efforts to weaken its enforcement) by serving as a bridge between grassroots feminist activists and legislative change, and her attempts to stop nuclear bomb testing in the Pacific Islands. This second part is the strongest of the book in clearly placing Mink as “ahead of the majority”: she opposed the Vietnam War (and the anti-Asian sentiment surrounding the war) from the get-go and was an early backer of Robert Kennedy in 1968 due to her belief that he, not Lyndon B. Johnson, was the best candidate to end the war. Mink also campaigned against nuclear bomb testing in the Pacific Islands in an early instance of protesting environmental racism. The effects of nuclear tests by the US government could potentially cause health issues for residents on the islands outside the blast zone due to wind. Mink felt strongly that the inhabitants of those islands, largely indigenous, deserved to not be put at risk.

The third and fourth parts of the book cover Mink’s life between congressional stints and her return to Congress. After giving up her House seat to run for Senate in 1976, which she did not win, Mink served briefly as the Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs. Unhappy with this position, Mink then served as the president of the Americans for Democratic Action for three years before returning to Hawaii, where she sat on the city council. Mink again won election to the House of Representatives in 1990, where she served until her death in 2002. During her second foray in Congress, Mink fought to strengthen workplace protection for women in the aftermath of the Anita Hill hearings, attempted to prevent neoliberal reforms to the welfare system based on prejudicial perceptions of those who received government benefits, and repeatedly attempted to include immigrants into citizenship rights despite rising anti-immigration sentiment beginning in the late 1990s.

With so much context for Mink’s legislative work, Wu deftly provides a brief explanation of relevant information without getting bogged down with the details. The Vietnam War was an extremely long and complex war, but the book only provides the relevant details for Mink’s specific actions attempting to end the war. There are times when a bit more context would have been beneficial, however. When describing the energy crisis of the 1970s, for example, Wu merely states that The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) announced an embargo against countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, leading to fuel shortages. While this is a difficult thread to completely untangle, and it is not necessary to do so here, more background on the US reliance on oil from OPEC would have benefited the discussion on the resistance to Mink’s efforts to regulate strip mining during the energy crisis of the 1970s.

Fierce and Fearless is an excellent work that demonstrates how historical moments touch each person’s life. In history education, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that every event affected real people. With this book, you see how one person (and their immediate family) lived through the Hawaiian plantation system, Hawaiian statehood, sexism, racism, the Vietnam War, Second and Third Wave feminism, the 1970s energy crisis, 9/11, and more. This biography provides an excellent primer on 20th century US history while exploring in-depth the life of one amazing woman.

Codee Scott is a Doctoral Candidate at Texas Christian University. She studies early 20th century American history and focuses on female entrepreneurship.