Abstract: This essay offers an account of the contemporary treatment of transsexuals in Iran, situating the official process in a discursive nexus that includes the law and psychology as well as psychiatry, and is engaged in establishing and securing a distinction between the acceptable “true” transgender/sexual and other categories that might be confused with it, most notably the wholly unacceptable category of the “true” homosexual. In this process, the category of “transgender/sexual” is made intelligible as an acceptable form of existence by the condensed working of the legal, the Islamic jurisprudential [fiqhi], the bio-medico-psycho-sexological, and the various contingents of the forces of coercion – which we often call “the state” — that is, necessarily and simultaneously subject to it. The analysis suggests that this complex nexus constitutes and authorizes a category of non-normativity as a legitimate acceptable category, a process of subjection which is partly based on transgender/sexuals’ own actions and therefore also self-definitions and self-productions. In all of this, distinguishing between “trans-” and “homo-” has become a critical marker.

On January 6th, 2010, the director general of the Office for the Socially Harmed at the Welfare Organization of Iran, announced that after two years of investigation and consultation with Military Service Organization, the code under which transsexuals would now receive exemption from the required military service had been changed from mental disorders to glandular disorders.[1] Transsexuals often referred to exemptions received under mental disorders as red exemptions, because becoming marked by mental disease made one virtually unemployable. On the other hand, glandular disorder is considered benign by employers.

See the websites of the Islamic Republic of Iran, State Welfare Organization (http://behzisty.ir/News/Show.aspx?id=7313, accessed January 14, 2010) and the Military >Service Organization of Iran (http://www.nezamvazifeh.ir/index.php?do=cat&category=peaeshki, accessed January 14, 2010).

Like many other domains of law, legal codes concerning procedures for medical examination of persons subject to army conscription and grounds for issuing exemption from service were revised after the 1979 revolution and new legislation was passed in 1989 (Ashrafian Bonab 2001: 413–29). The army conscription law has been under discussion for revision over the past two years. A new legislation is currently under consideration in the Majlis.

On the face of it, one could read this announcement as one more step taken by the Iranian government to re-arrange this subject population within a pathologizing taxonomy. And indeed, it is that too. Yet, thousands of hours of trans-lobbying had gone into producing this seemingly innocuous legal change. In the previous several years, a small dedicated group of activists lobbied, demanded, and negotiated various policies. With remarkable skill, they navigated, and developed allies in, numerous committees that had been assigned various tasks related to their medical, legal, and social needs.

Against the backdrop of a dominant reading, in which contemporary procedures for transsexuality in today’s Iran are attributed to the state’s policy of homicidal homophobia, my alternative account is a more complicated history in which trans-activists have been a critical player. Trans-activism, far from being a state-driven and controlled project is part of the process of state-formation itself [2] –an on-going process that continues to shape and re-shape, fracture and re-fracture, order and re-order what we name “the state.”[3]

Like Ferguson and Gupta (2002: 989), my approach to the study of Iranian state emphasizes the productivity of its disciplinary and regulatory work.

As George Steinmatz has put it,“Sometimes state-formation is understood as a mythical initial moment in which centralized, coercion wielding, hegemonic organizations are created within a given territory. All activities that follow this original era are then described as “policy making” rather than “state-formation.”But states are never “formed” once and for all. It is more fruitful to view state-formation as an on-going process of structural change and not as a one-time event.” (1999: 8–9)

The press coverage of “trans” phenomena, both in Iran and internationally, increased sharply in early 2003, and continued intensely over the next five years.[4] The celebratory tone of some of the early international reports –welcoming recognition of transsexuality and the permissibility of sex-change operations –was sometimes mixed with an element of surprise: How could this be happening in an Islamic state? In other accounts, the sanctioning of sex-change became tightly framed through a comparison with punishment for sodomy (a capital offense) and the presumed illegality of homosexuality –echoing some of the official thinking in Iran.[5] For legal and medical authorities in Iran, sex-change is explicitly framed as the cure for a diseased abnormality, and on occasion it is proposed as a religio-legally sanctioned option for heteronormalizing people with same-sex desires and practices. Even though this possible option has not become state policy (because official discourse is also invested in making an essential distinction between transsexuals and homosexuals), international media coverage of transsexuality in Iran has increasingly emphasized that sex-reassignment surgery was being performed coercively on Iranian homosexuals by a fundamentalist Islamic government.

The international effect of these television and video documentaries obviously deserves more than one line noting their quantity, but this is not a task I take up here or in my book.

I say “presumed illegality of homosexuality,” because what is a punishable offense are sexual acts between members of the same sex, with anal penetration of one man by another (liwat/lavat/sodomy) being a capital offense. In international coverage, liwatis almost always translated as homosexuality. The ubiquitous use of “homosexuality” and “homosexual” to refer to all kinds of desires and practices between usually male-bodied persons, whether by historians, ethnographers, journalists, or rights activists, does not serve either scholarship or necessarily possibilities of living better lives in contemporary Iran. For a thoughtful critique of politics of such namings, see Long2009.

At their best, the readings of transsexuality in Iran as legal and on the rise because of impossibility of homosexuality work with a reductive Foucauldian concept of “the techniques of domination,” in which subjectivity is constituted by governmental designs and hegemonic power.[6] I remain cognizant of and map out some of these techniques in contemporary Iran. Yet I lean toward highlighting how such techniques become at once productive of “the art of existence.” Indeed, their work of domination depends on their productivity for the art of existence.[7]

Prosser critiques arguments that tend “to emphasize the transsexual’s construction by the medical establishment … [in which]the transsexual appears as medicine’s passive effect, a kind of unwittingly technological product: a transsexual subject only because subject to medical technology” (1989: 7). Similarly, the understanding of Iranian transgender/sexuality as contingent upon religio-legal impossibility of homosexuality is conceptually akin to what Prosser notes for reading Stephen’s transgenderedness (in Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness) as a pre-history of lesbianism at a time that the latter could not speak its name, “the implication is that lesbianism is the true trans-historical subject, while the transgendered paradigm is the culturally contingent investiture” (Prosser 1989: 137).

For an insightful discussion of “the techniques of domination” and “the art of existence,” see Heiner (2003).

What transsexual as a “human kind” –to use Ian Hacking’s concept –means today in Iran is specific to a nexus formed not simply by transnational diffusion of concepts and practices from a Western heartland to the Rest.[8] It is as well the product of socio-cultural and political situation in Iran over the previous half a century. Living a transsexual life in Iran carries a particular set of affiliations and disaffiliations that are specific to this national-transnational nexus. The distinction between the (acceptable) transsexual from the (deviant) homosexual, for instance, has been enabled by bio-medical, psychological, legal, and jurisprudential discourses that were formed between the 1940s and the 1970s.

I take the concept of “human kind” from Ian Hacking: “By human kinds, I mean kinds about which we would like to have systematic, general, and accurate knowledge; classifications that could be used to formulate general truths about people; generalizations sufficiently strong that they seem like laws about people, their actions, or their sentiments” (1995: 352). As he further elaborates,“[Human kinds] are not just part of our system of knowledge; they are part of what we take knowledge to be. They are also our system of government, our way of organizing ourselves; they have become the great stabilizers of the Western post-manufacturing welfare state that thrives on service industries. The methodology of making “studies” to detect law-like regularities and tendencies is not just our way of finding out what’s what: “studies” generate consensus, acceptance, and intervention.”(364–5)

In the discourse of national scientific progress of the 1930s and ‘40s, trans-bodies emerged as affiliated with,yet distinct from,congenital intersex bodies,and sex-change medical interventions were discussed as examples of advancements in medicine and surgery.

This discourse worked with the emerging psycho-behavioral science’s discourse of sexuality that incorporated all bodies in its concern with the health of the nation, the progress of its educational system, and the reform of family norms. A growing academization of vernacular psychology and sexology of these earlier decades resulted in the dominance of physio-psycho-sexology within the medical and health scientific community by the late 1960s, which contributed to the disarticulation of transsexuality from the intersex, and its re-articulation with homosexuality. Transsexuality became re-conceived as a particularly extreme manifestation of homosexuality.

Physio-psycho-sexology also informed the emergent criminological discourse, such that sexual deviance was diagnosed as potentially criminal. Treatises on criminal sexualities described male homosexuality as almost always violent, akin to rape, prone to turn to murder, and almost always aimed at the “underage.” This association of existing sexual practices between older men and male adolescents with criminality continues to inform dominant perceptions of male homosexuality in Iran and haunts transwomen lives even post-op.

The 1979 revolution and consolidation of an Islamic Republic produced a paradoxical situation for transsexuality: it immediately made what we would name transgendered lives impossibly hazardous. At the same time, it led to transsexuality’s official sanction. In the 1970s, “woman-presentingmales” had carved themselves a space of relative acceptance in particular sites and professions. The 1979 revolution, and in particular the cultural purification campaigns of the first few years, ruptured the dynamic of acceptability and marginalization of “the vulgar” and “the deviant” accorded them by the larger society. Now, “woman-presenting males” not only carried the stigma of male homosexuality, but they also transgressed the newly imposed regulations of gendered dressing in public. Simultaneously, the establishment of an Islamic Republic set in motion a process of bureaucratization, professionalization, and specialization of Islamic jurisprudence, and the Islamicization of the state that has made the current transition process possible.

At present, the transition process works around a notion of “filtering” –a 4-6 month period of psychotherapy, along with hormonal and chromosomal tests –the stated goal of which is to determine if an applicant is “really transsexual,” “really homosexual,” intersex, or perhaps suffers from a series of other classificatory disorders. A Commission at the Tehran Psychiatry Institute makes a diagnostic recommendation to the Legal Medicine Organization of Iran, whose board of specialists makes the final decision and issues, if approved, the much-hoped-for official certification of one’s status as transsexual.

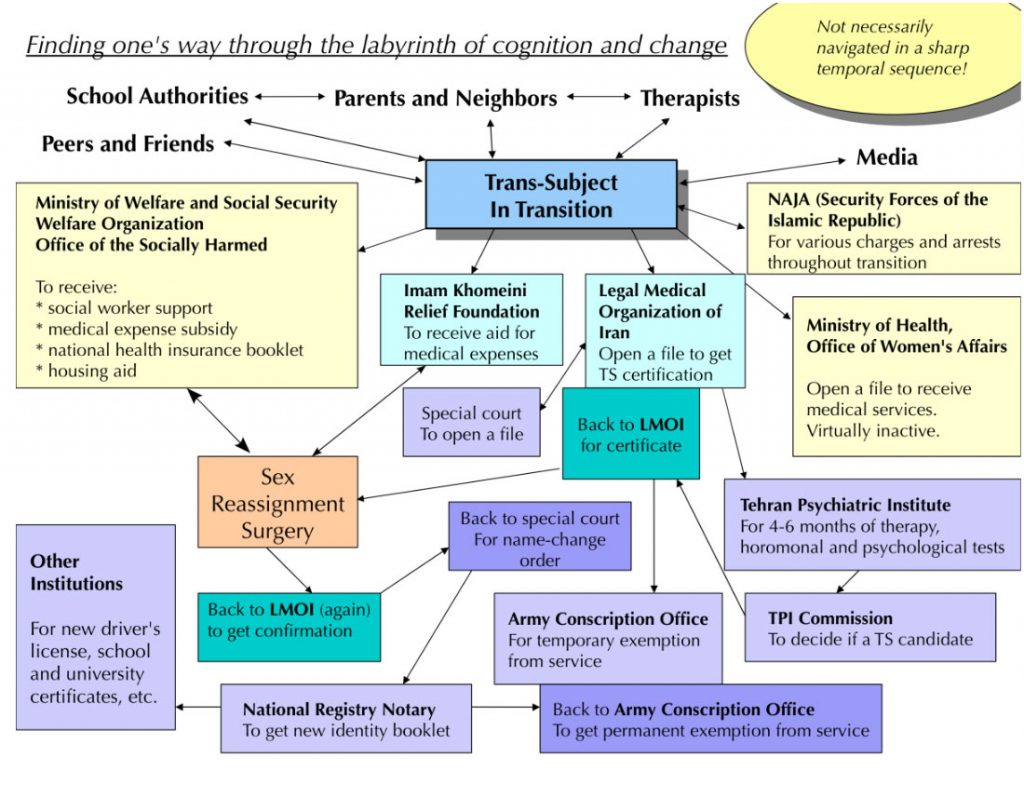

This much-sought-after certification is the legal document that opens numerous doors for transsexuals. Not only does the certificate authorize the permissibility of hormonal treatment and sex reassignment surgery, it also entitles one to basic health insurance (state provided), financial assistance (for partial cost of surgeries and for housing aid), and military service exemption. The Legal Medicine Organization of Iran also instructs a special court to approve the name change of the certified person (post-SRS), which entitles the person to receive new national identification papers.[9] Figure 1 maps the complicated labyrinth of socio-institutional sites one has to navigate.[10]

Once the LMOI confirms that a person has changed sex, a court ratifies that confirmation and orders the Registry (of Ahval, of birth and other life events such as marriage, divorce, children, and finally death) to issue a new book of identification, in which the old name is not recorded, but there is a clause in the explanatory page of the new booklet saying this person has changed name. None of these have been simply state handouts. Countless hours of lobbying by trans-activists have been put into getting every single one of these changes. Nor can any of these gains be taken for granted; various state, medical, and religious authorities have their own agendas. At times, some of these overlap with the transcommunity’s agenda. At other times, there is conflict, which the activists have opted to pursue by finding allies within various government institutions and learning how to play one against the other.

Special thanks to Kirsten Wesselhoeft for changing my squiggles into a graph.

This complex nexus constitutes and authorizes a category of non-normativity as a legitimate acceptable category, a process of subject-formation/subjection which is partly based on transsexuals’ own actions and narratives, and therefore also self-cognition and production.

Before the 1979 revolution, and before the consolidation of the Islamic Republic in the 1980s, the scientific community was neither aware nor generally concerned with Islamic rulings on medical matters, including the issue of transsexuality. By the mid-1980s, however, it became clear that the bio-medical and psycho-sexological sciences needed to present their reasoning about transsexual matters in a different style to be able to interact with Islamic legal authorities when so needed.

When it comes to sex-change, as it is with many other issues, there is no unanimity of opinion among fatwa-issuing Shi‘i scholars in Iran.[11] All consider surgeries on the intersex permissible [because it brings out “the hidden genus” of the body]. Some explicitly argue against non-intersex sex surgeries, while others express doubt about its permissibility.

The Sunni scholars’ view on this subject has a different history and current configuration.

Regardless of these differing stances, it was the overwhelming weight of Ayatollah Khomeini’s own fatwa that translated into law. This weight cannot be understood as a matter of religious authority; it was an authority derived from his unique position as leader of the most massive revolution in late twentieth century.[12] While the Iranian constitution has codified the position of the supreme jurisprudentas the pinnacle of power, only Khomeini in fact had the combined religious and political authority that would translate his jurisprudential opinion into law.

Here lies also the significance of re-issuance of his fatwa on permissibility of sex-change after the revolution. Unlike the earlier opinion issued in the 1960s, which had gone largely unnoticed, the mid-1980s ruling became productive of state law. Today, even though Ayatollah Khamenei is the Supreme Leader, the weight of his religious fatwas is no different from those of many other grand ayatollahs of similar rank. The Compliance of all legislation with Islamic concepts is supervised not by him but by the Council of Guardians.

Khomeini’s ruling in Tahrir al-wasilah, a mid-1960s text, appears under a section on “The Examination of Contemporary Questions,” within which a subsection is devoted to “The Changing of Sex.”[13] It reads in part:

Tahrir al-wasilah was apparently written in 1964–5, during the first year of Khomeini’s exile to Bursa, Turkey. It was published only after his move to Najaf in late 1965. I am grateful to Maryann Shenoda for the translation from the Arabic of this section of Tahrir al-wasilah, which I have slightly modified.

The prima facie view is contrary to prohibiting the changing, by operation, of a man’s sex to that of a woman or vice versa; likewise, the operation of a hermaphrodite is not prohibited in order that s/he may become incorporated into one of the two sexes. Does this [operation] become obligatory if a woman perceives, in herself, the inclinations which are among the type of inclinations of a man [lit. the root/origin inclinations of a man], or some qualities of masculinity; or if a man perceives, in himself, the inclinations or some qualities of the opposite sex? The prima facieview is that it is not obligatory if the person is truly of one sex, and changing his/her sex to the opposite sex is possible.[14]

Khomeini 1967 or 8, volume 2: 753–5.

The double negative in the first sentence, “contrary to prohibiting,” and the concluding “not obligatory” are the critical terms that have defined the dominant views among top Iranian Shi‘ite scholars and most importantly have defined the legal procedures for sex reassignment. From the point of view of transsexuals, this conceptualization has opened up the space for acquiring the certificate of transsexuality without being required to go through any hormonal or somatic changes if they do not so wish. This continues to be a subject of much contestation between transsexuals and various state authorities. Legal and religious authorities know fully well that many certified transsexuals do very little, beyond living transgender lives, once they obtain their certification; at most they may take hormones. While the authorities do not like this situation, they cannot overrule Khomeini’s double negative.

In contemporary discussions, the notion of jins [genus/sex] travels between two distinct registers: the classical Islamic meaning of jins as genus of something and the notion of sex (jins) in its modern sense. The transformation of socio-cultural notion of sex/gender over the past century has brought into proximity the male/female distinction of Islamic jurisprudence with the biological sex taxonomies and social categories men and women. This proximity has enabled the convergence of some jurisprudential thinking with the bio-medical and psycho-sexological discourse about transsexuality. But Shi‘i scholars are also trained to keep these categorical distinctions apart. These definitional distinctions enable an Islamic scholar such asHujjat al-Islam Karimi-niato argue against those Islamic scholars who oppose sex-change on the basis of opposition to changing God’s work of creation. He argues that change of male to female and vice versa is not change in genus of a created being; it is a change in his/her sexual apparatus.

A jurisprudential challenge arises when the person is in transition. How does one deal with “the discordant subject,” with the “lack of correspondence between gender/sex of soul and body,” as Karimi-nia’s concept of transexuality would have it? Does one go by the gender/sex of the body or that of the soul? Here, transsexuals insist on going by the soul. Karimi-nia, on the other hand, wary of the intrusion of “same-sex-gaming” [hamjinsbazi, the pejorative Persian word for homosexual practices] that haunts Islamic jurisprudential thinking on this subject, leans on going by the gender/sex of the body. But here jurisprudential caution cannot sanction legal closure: what is permitted [halal/mubah] cannot be made into required [vajib],short of a fatwa issued by a mujtahid who has complete hegemony over jurisprudential opinion. In Iran’s recent past, only Ayatollah Khomeini enjoyed such politico-religious authority. Since his death, no one comes anywhere close to him.

This situation continues to allow a domain of murkiness for living non-hetero-normative lives. The closest the authorities have come to attempting to tighten the regulations concerns the timing of issuing new name-changed identification papers. Usually,transsexuals, especially FtMs, apply for new identity documents after the initial operations. They obtain letters from surgeons certifying that they have done their SRS; sometimes courts have required bodily examination, something that transsexuals have found humiliating and resisted. After much lobbying by trans activists, the courts have finally been instructed to accept physician certification.

The attempt to refuse new documents till completion of reconstructive surgeries has also created vehement reaction because of the state of surgically skilled professionals available in Iran. Moreover, a common concern both for FtMs and MtFs is financial. Unless the government would be willing to cover total cost, the legal requirement would be unenforceable. It is this complicated imbrication of considerations of state and requirements of religion that provides negotiating and resisting spaces for transsexuals.As one FtM put it, “Once I was diagnosed as trans, I started having sex with my girlfriend without feeling sinful.”

Karimi-nia’s reiterated insistence that “a Great Wall of China” separated transsexuals from same-sex practitioners at one level is counter-intuitive: Nowhere in Islamic jurisprudential texts transsexuals and homosexuals are proximate categories requiring a separating border; transsexuals, as we have seen,are placed in proximity with the intersex.How then have transsexuals acquired proximate status to homosexuals, not only in hostile opinion, but also in the thinking of a trans-friendly scholar such as Karimi-nia? This proximity has been shaped through the coming together of domains of science and Islamic jurisprudence. While in classical jurisprudential thinking, there may be no reason to ever connect these two categories, contemporary Islamic thought does not take shape in some seminary-isolated space; Karimi-nia’s thinking has in part been shaped through conversations with doctors and psychologists, within whose domain of thinking transsexuality and homosexuality do indeed constitute neighboring categories. The work of these other registers contributes to creating a single logic of categorization, keeping all gender/sex variant desires and practices into close proximity.Moreover, the sexological categorization receives visual confirmation in self-presentation of many transsexuals, through often indistinct living styles of trans-and homo-sexuals.

Karimi-nia’s central perception of transsexuality as a disparity between gender/sex of body and soul is empowered by a slippage between psyche and soul that has marked the entry of psychology into Persian-language Iranian discourse since early decades of the 20th century. Such slippages and murkiness over soul and psyche enable alternative outlooks on transsexuality among psychologists who share with Islamic scholars such as Karimi-nia a view of transsexuality as discordance between psyche/soul and the body. It also enables the contemporary traffic between psychology and the older sciences of religion [‘ulum al-din]; among healers of psyche and guardians of souls. That psyche and soul have the ambiguous relation that they do is what allows Karimi-nia to translate psycho-sexological concepts of transsexuality back into gender/sex discordance between soul and body; it provides a way to address transsexuality as a psychological condition in Islamic terms. Moreover, the concept of discordance between soul and body is more benign and less pathologizing –thus more appealing to transsexuals –than that informed by psycho-sexological discourse of gender identity disorder.

Let me conclude with some reflections on challenges of translation. When it comes to issues of sexual/gender identification, desire, and practices, a single concept –linguistically and culturally [jins] –keeps them together.[15] Not only has no distinction between sexuality and gender emerged, but more significantly, lives are made possible through that very non-distinction. The tight conjunction among sex/gender/sexuality has both enabled the work of changing the body to align its gender/sexuality with its sex and has set the parameters within which these changes are imagined and enacted. It has therefore necessarily contributed to the structure of self-cognition and narrative presentation among transsexuals. More specifically, the persistent pattern of a tight transition from a cross-gender-identified childhood to an adolescence marked by sexual desire for one’s own peers speaks to the indistinction between gender/sex/sexuality. This indistinction regularly disrupts attempts to separate the homosexual from the transsexual, even as that distinction is regularly invoked.

This is by no means unique to Iran, of course. Lawrence Cohen makes a similar point: “I collapse the terms sex and gender here … confronted with narrative and language which resists any a priori divisibility into embodied sex and expressive gender” (Cohen 1995: 278). Megan Sinnott has similarly noted, “there is virtually no linguistic distinction in Thai between sex (as in body) and gender (as in masculinity and femininity)” (Sinnot 2004: 59). In Persian academic texts as well as in mass media, jins and its various related conjugations are used for both gender and sex.

The issue of change of concepts traveling from one history and context to another does not pertain to “just words.” The current procedures of diagnosis and treatment for transsexuals in Iran are based on DSM-III and IV and a number of US-designed tests. The dominance of American scientific discourses, training, and procedures has transported many of these concepts globally. Because of their status as science, they arrive at their destination as dis-located, as if with no history of origin. Their re-embedding in the local Iranian context, at the particular historical moment of the past two decades, transforms their meaning and produces specific effects in that acquired location. What work does the import do in its local context, in relation to the many other concepts and practices that it becomes intertwined with and that inform its meaning in the transplanted space?[16]

Tani E. Barlow (1994: 253–89) has a similar approach, from which I have learned greatly.

The destination setting includes a different concept of self. What does saying “I am trans/gay/lesbian” mean when the question of “what am I?” does not dominantly reference an I narrativized around a psychic interiorized self, but rather an I-in-performance at a particular nexus of time and place? In a socio-cultural-historical context in which the dominant narratives of the self are formed differently from that which has become dominant in much of the domain we name the West, how does one understand the seemingly similar emergences of concepts and practices labeled gay, lesbian, transsexual? What concept of self informs the various styles of (self-) cognition, individual subjectivities, as well as the relations between individuals and their social web including state institutions? What are the implications of recognizing these differential situated meanings of words for building alliances internationally on issues of sexual rights?

Author Bio: Afsaneh Najmabadi is the Francis Lee Higginson Professor of History and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard University. Her book, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), received the 2005 Joan Kelly Memorial Prize from the American Historical Association. Her latest book, Professing Selves: Transsexuality and Same-Sex Desire in Contemporary Iran (Duke University Press, 2014) was a finalist for Lambda Literary Award in 2014, received the 2014 Joan Kelly prize from the American Historical Association for best book in women’s history and feminist theory, and was a co-winner of 2015 John Boswell prize, LBGT History, American Historical Association. Najmabadi leads a digital archive and website, Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran (www.qajarwomen.org). The project has been awarded five two-year grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities.