Abstract: In this creative essay, we draw on a study conducted with three Black girls engaging with arts-based methods. We show how the youth ideas supported participatory feminist research. Drawing inspiration from the accordion style artwork the girls developed, we insert another layer of visibility by interspersing the girls’ conversations with other Black feminists on the subject of the Black (girl) gaze and Black student Math world making. This project speaks to what Katherine McKittrick (2021) asserts in her book, Dear Science and Other Stories where she asked, “what happens to our questions if we insist our methodologies are, in themselves, forms of black well-being? … What if there is not a learning outcome?” (p. 117). Essentially, in this project, we did not set out to have a learning outcome but rather we created a space where the girls could interrogate the representation of Black [girls] learners in mathematics education. In this way the girls approached and operationalized their artmaking as a form of change making.

2019 The World

When Disney announced the casting of Halle Bailey in The Little Mermaid, racist remarks exploded on the internet which continued when the live action flick was released in 2023. The issue raises the question of where Black people are allowed to be, as some find it challenging to conceive of Black people simply existing in the realm of fantasy and fiction.[1] The three Black girls (Mariam, Nadia, and Zainab) who partnered in this research program, alongside the co-authors (Molade and Myrtle), asserted themselves by centering their belonging in mathematics learning spaces.

2023 Research Space[2]

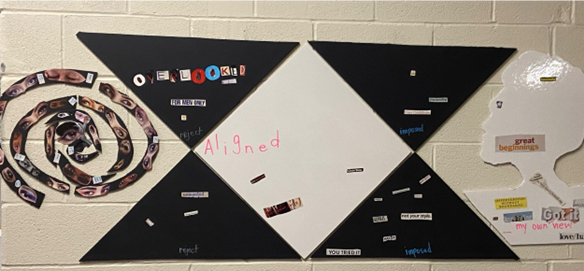

The energy in the room began quiet and grew slowly with the arrival of each student. Mariam, Nadia, and Zainab took their usual seats around the long table in the middle of the room. By now we had heard from each of them about what this space, both in its physical offering and in its offering of ease, expansiveness, and comfort meant to them. We saw the ease with which they seemed to claim the same week after week and the quiet camaraderie that had developed between them. The girls had met weekly to interrogate their math spaces through engaging in collaging (see Figure 1) and other types of artmaking that revealed their relationship to math, math representation, and dreaming up mathscapes where they were represented in their fullness.

This final session began with Molade checking in with the girls about the details of their school life and quickly moved to a discussion on what the girls had taken away from the experience. There was an excitement in the room and a looming goodbye.

Molade asked the girls what they took away from the experience, and, at first, they seemed to stumble looking for words that would describe an experience that turned out differently from their expectations. Initially, they thought the sessions were about offering math support in school.

Eventually, Nadia pointed towards the Gaze Matrix (see Figure 1) – “The Gaze Matrix really brings things out to me…”

As Nadia paused to think a little more about her response, Myrtle recognized that these feelings were difficult for the girls to talk about and synthesize and watched as they struggled to name the injury they felt.

Nadia continued, “The Gaze Matrix gave me a better understanding of how things can be imposed, rejected, and how things line up with it”.

In nine weeks, the girls explored the ways they were seen and saw themselves in math spaces using arts-based methods to communicate their experiences. Molade asked the girls to reflect on this experience.

Nadia responded, “It was (about) our thoughts and opinions.”

Myrtle asked, “Is that something you are commonly asked about–your thoughts and opinions about things?”

Nadia quickly responded with a sharp “No!”

The room came alive again with laughter that spoke more of an understanding rather than humour. Molade and Myrtle recognized this experience as being part of many Black girls’ experiences. Nadia continued and provided more information.

“If anything, it didn’t feel like research, but it felt like having conversations. Like research you don’t expect.”

Math & Me: How They See Me

In the first part of the research space, Mariam, Nadia, and Zainab reflected on their experiences as mathematics learners in high school, where they filled out the gaze matrix (Figure 1). “Finding the words” to their experience supported the girls in their ability to name their experience and examine whether the words they chose were ones they internalized (alignment) or words that they rejected. These words were placed on “The Gaze Matrix” which was attached to the wall in the loft space throughout the project. This wall would serve as a reference point for discussions. Drawing inspiration from the accordion style artwork (Figure 2) the girls developed, we insert another layer of visibility by interspersing the girls’ conversations with other Black feminists[3] on the subject of the Black (girl) gaze and Black student Math world making.

bell hooks:[4]Spaces of agency exist for black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see. The “gaze” has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black people globally.

Nadia: And then, yeah, because like, I feel like they look at a lot of students, like, slow learners.

Katherine McKittrick:[5]We know more than the abjectness projected upon us. We are not obsequious. We are not abject. We know more. We know. We know ourselves.

Zainab: For example, let’s say we’re doing a math question, and they say, oh, out of all three of us in a group. One person has to answer the question. I don’t think I’d be anyone’s first pick for my own to be honest. So, we’re not anyone…Because I remember like this one time. Like, I said, it was one person out of the whole group who had to answer the question, and this girl was really eager to do it. So, whatever, like she was allowed to answer the question. And then I could see she got it wrong. And I try to tell (her) here, like, hey, something’s wrong here. And she was so confident in her answer until the teacher actually said no, like this is wrong.

Katherine McKittrick:[6] What is it about space, place, and blackness—the uneven sites of physical and experiential ‘difference’—that derange the landscape and its inhabitants?

Nadia: Um, I feel like they just see me as, like, a regular student. Like, every other student.

But at the same time, they, know that I’m one of the students that puts in a lot of effort. Yeah.

Math and Media: What We See

In the second portion of the research, Mariam, Nadia, and Zainab reflected on the ways various media constructs Black mathematics learners. We watched clips from TV shows like A Different World to explore the learning experiences of Whitley, a Black female student who struggled in mathematics. We also read snippets of Nnedi Okorafor’s Africanfuturist novella, Binti. Lastly, we asked the girls to search on social media for representations of Black girl math learners.

bell hooks:[7]The prolonged silence of Black women as spectators and critics was a response to absence, to cinematic negation.

Nadia: I started to do…a little research about it, right? So, yeah… like, this is actually, really true, is there, something, that’s wrong? Like, why can’t… I search (up) black people, black teachers, thinking (about) math without, like, you know, being, coming across, (only) like, Asian person or a white person, you know?

bell hooks:[8]To stare at the television, or mainstream movies, to engage its images, was to engage its negation of Black representation.

Mariam: I think one of them from when we were talking about the TV shows. We were talking about how the Black character in the show was either really quirky, and kind of just there to just say one-liners. And that was kind of their whole personality, or they were just there to be smart. It was like, we couldn’t have a balance of like a normal character. And then also how, either way, it was always that character that was always of a lower class than whoever the show was about generally. And how often, if it wasn’t strictly like a black producer or a black director, how it would always be the side character that was black and never the main character.

Nadia: You see how, like, (the) majority of, the teachers were, either white or Asian, right?

And now that I look at it, maybe they only hire certain races, I think, I don’t know, because, like, every math teacher in my school is Asian. There’s no different race or ethnicity. There’s just one. I noticed, on the grade 9 teacher, the grade 10 teacher, the grade 11 teacher, the grade 12 teacher, they’re like, Asian. And I feel like they look at the black youth, like, different. Because, I know, some, black youth don’t really try, they just get their work, and they don’t do it…

Audre Lorde:[9] In the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear–fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgment, or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation. But most of all, I think, we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live. Within this country where racial difference creates a constant, if unspoken, distortion of vison, Black women have on one hand always been highly visible, and so, on the other hand, have been rendered invisible through the depersonalization of racism.

Mariam: Um, I think a bit, because I feel like I’m not, I’m not like a bad math student, but I’m generally quiet in class. And even if I know what I’m doing, and I really understand the subject, like I know we just did finance. And I remember I was really good at that. But, I think it was always just expected to be the same people answering the questions. So like, I guess I kind of just decided not to raise my hand, which is still on me. But like, I still, I guess it was kind of something where it’s like I expect to be overlooked in them. And another person who always has those questions to answer the questions, to that extent, if that makes any sense.

bell hooks:[10] I remembered being punished as a child for staring, for those hard, intense, direct looks children would give grown-ups, looks that were seen as confrontational, as gestures of resistance, challenges to authority. The “gaze” has always been political in my life. Imagine the terror felt by the child who has come to understand through repeated punishments that one’s gaze can be dangerous. The child who has learned so well to look the other way when necessary. Yet, when punished, the child is told by parents, “Look at me when I talk to you” – only, the child is afraid to look. Afraid to look but fascinated by the gaze. There is power in looking.

Mariam: When we were looking up mathematicians, I remember, we would come across a lot of just European, uh, men. And I think it would be kind of cool to see like, how different, like, places in the world or different, like, cultures, what, what they added to that subject, kind of, I guess that would be.

Nadia: I don’t, yeah, I don’t see math, I don’t see math in my culture. Because my culture, we see, English more, you know… we don’t see math, when it’s like, if you’re talking about math, the only math they’re talking about is money math, okay?…So, they would always think, they even still think English, math, science, and all those are, still are American, Canadian, Europe thing. They don’t think it’s their culture.

bell hooks:[11] Most of the black women I talked with were adamant that they never went to movies expecting to see compelling representations of black femaleness. They were all acutely aware of cinematic racism—its violent erasure of black womanhood.

Math & Me Part 2: How We Want to Be Seen

In the final portion of the study, the girls created another artwork (Figure 2) that further explored how they are seen in contrast to how they want to be seen as Black math learners. We took headshots of the girls and printed two black and white copies of the photo. We asked the girls to keep one image as is and they colored and included words that represented how they wanted to be seen. This activity created two views of the girls using an accordion style optical illusion where two pictures are visible based on vantage point. Depending on which side of the image the viewer stood, they would either see the black and white image with words that described how students are seen or the colorful image that described the fullness of how they would like to be seen in math spaces in school.

Nadia: Um, yeah, you see how, when you told us to, write like a bunch of words that, to, describe yourself, right? And color in. So, when I was describing myself, a lot of people don’t know themselves, right? So, I had to really think hard about how people see me, right? Because I don’t know how I am to people, right? So, I had to really think hard, how, how do I really ask, deep down, you know, this is really me, you know, I don’t know. So, I had to, it was really, I was really overthinking it. You know? Because describing yourself is actually pretty hard.

Nadia: I don’t want people to think that I’m a slow learner because I feel like when it comes to, like, black students, they think, oh, they don’t want to learn. They just want to, you know, be in class or … they just want to come to school to do nothing. I just want people to think I’m trying to, you know, (to) be one of the students that are graduating high school and stuff because you know, how they say a lot of black students don’t graduate and stuff. I just don’t want them to think … I want them to think differently. I don’t want them to think in a negative way.

Tina Campt:[12]So, how do we live the future we want to see now when confronted with the statistical probability of premature black…mortality? How do we create an alternative future by living both the future we want to see, while inhabiting its potential foreclosure at the same time?

Zainab: I always want to be seen as someone who’s ready to learn, you know. I have a lot of goals in high school. After two months, it’s going to be two years of me being in high school, which I feel like… It sounds like a long time, but time really does fly by so fast. And there’s a lot of things I want to accomplish. I want to get more school involved; you know. Maybe make my own like a math club or something like that. It will be for people of color and like Black students, you know. Yeah, there’s a lot of things I wanted to… And I kind of want to be valid. I don’t know yet, but yeah.

Zainab: I feel like it was just kind of a statement to everything that we’ve discussed, and it was just truly like about us in the end, you know.

Zainab: I don’t know if I’ve told you guys yet, but math is honestly probably my favorite subject. And I think my sense of just loving it. It came from my parents, to be honest, because they really love it too. Like I remember being younger, and sometimes I didn’t understand things, so I go to my parents about it. They’d explain it so well to me in a way where it’s like. Wow, like the teacher cannot have done this the way you guys have, you know.

Mikki Kendall:[13]My great-aunts were educated, though my grandmother left college during the war, and there’s a weird story about her working for the US Army Signal Corps that might in fact be a cover for her working in cryptanalysis. Dorothy loved her puzzles and her mysteries and her codes, and she was frankly a genius who never got the credit she probably deserved. But she raised strong, smart children. Complicated children, but still, she made sure that she knew what price was paid to get us here.

Zainab: Oh, yeah. Basically, at my school, they do things like awards and stuff. And we have a whole ceremony thing for it. So, I remember, I think the math award went to a grade 12 girl, who was like Black and Muslim. So, it kind of resonated with me a little bit. It was like, oh, that needs to be me in the next year.

Nadia: Because I just, I see like two futures of me. It’s a picture of two futures of me, and like, I noticed, you know, when you notice something in yourself, when you have two sides. I have some sides in the picture as well. Right? So one was positive, and then one was the dark, you know? Like, I have two personalities in the picture. It was color and no color. Like, I don’t know, it’s maybe that’s how I am in real life, you know?

Nadia: I want to be seen, I want people to know that I understand math. And I don’t want to think that I’m a slow learner.

Mariam: Well, I think I want to be seen. I mean, I said I’m quiet, but I’d like to be seen still trying because I feel sometimes when they associate like, quiet people with like, people who don’t try or like who care less or something when we just don’t want to talk in class. And then I think it’d be kind of nice if they maybe stop and asked around “does everyone get this?” And then, or ask individually if different people understand because they might be quiet in class and then moving on. I think that’s kind of it.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs:[14]What if school was the scale at which we could care for each other and move together?… I do commit to rigorously learning how to gracefully collaborate, and step back when it’s your turn with nothing to prove. I do commit to the work of going deep enough to find the necessary food that lights us up inside. I love you, and I have so much to learn. I love you and we are just now learning that it’s possible…I love you, and how generous–how downright miraculous–it is that life would let me learn like this.

Zainab: And it’s just like, I want to be seen like that in math. I know I had like a lot of bright, different colors. I want to be seen as someone, like a bright student, a bright learner. Like someone who wants to… is always eager to learn and like ready to learn different things. And isn’t, you know, silenced or like, you know.

bell hooks:[15] By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: “Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.”

Notes

[1] We used arts-informed practices to explore how Black girls reflect on their past and envision a present and future mathematics learning space within and outside colonial logics. The arts present opportunities to engage in gaze practices where Black girls can reflect on how they see themselves and how they are seen while developing “counter gaze” practices (Tina M. Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Boston: MIT Press, 2021)). Employing arts-informed methods is a decolonizing act insofar as it pushes against the logical structure of mathematics to embrace the “accumulative textures” (Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021)) of stories using creative arts that affirm Black livingness through embodied practices.

[2] We partnered with three Black girls in the Greater Toronto Area over nine weeks consisting of two-hour sessions. Mariam was in grade 9 at a French immersion school while Zainab and Nadia were both in grade 10 at a diverse school. The research project was divided into three segments: Math & Me focused on reflecting on their experience as mathematics students in high school; Math and Media approached the question of the role the media played in constructing Black youth identity relating to Math; Math & Me Part 2 circled back to where students began when they explored their relationship to math. This segment focused on reimaging and rebuilding liberatory futures in Maths.

[3] Inspired by McKittrick’s “textual accumulation,” Myrtle Sodhi, an artist-scholar, conceptualized the accordion style art creation and the subsequent layering design of the conversations with the girls and the Black feminists. See her dissertation “Black Women Equity Educators’ Journey from the Loophole to the Homeplace: A Kwik! Kwak! Approach” to learn more about her use of McKittrick’s “textual accumulation.”

[4] bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black American Cinema, ed. Manthia Diawara (New York: Routledge, 1993): 289.

[5] McKittrick, Dear Science, 486.

[6] Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006): 3.

[7] hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 291.

[8] hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 289.

[9] Audre Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984): 37.

[10] hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 117-119.

[11] hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 291.

[12] Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

[13] Mikki Kendall, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women White Feminists Forgot (New York: Penguin Books, 2020): 141.

[14] Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2020): 30-31.

[15] hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 289.

Author Biographies

Dr. Molade Osibodu’s (York University) research interrogates the enduring impacts of coloniality in [math] education, with a focus on the lived experiences of Black youth and educators in both Canada and Sub-Saharan Africa. Grounded in decolonial frameworks, Black geographies, and participatory research methodologies, her scholarship explores how mathematics curriculum, policy, and pedagogy are shaped by Eurocentric and racialized structures. Osibodu’s work spans three intersecting lines of inquiry: the experiences of Black youth in mathematics classrooms, the colonial foundations of curriculum including international education curricula, and the influence of popular culture on perceptions of mathematical belonging. Her recent projects, such as Envisioning Diasporic Mathematics Literacies and Critical Financial Literacy, offer critical insights into how Black learners navigate and reimagine mathematics education. She has shared findings with major stakeholders, including the Toronto District School Board and the Ontario Mathematics Coordinators Association, and has published in leading journals such as Educational Studies in Mathematics, Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, and the Comparative Education Review. Her research has been well-funded including by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council in Canada.

Myrtle Sodhi is a PhD student at York University in the Faculty of Education. Her research focus relates to Black feminist thought, precolonial African thought, and ethics of care and their roles in re-envisioning systems. Through the process of reclaiming her inherited Afro-Caribbean Indigenous storytelling role she uses her work to uncover stories located in the body. The Black body is often a site of personal, political, and social enactments and can reveal the complexities in re-creation and reclamation efforts. Her work examines these complexities while also providing a way to increase the capacity for self and community integration. Her (research) creation attends to a process that is guided by trans-temporal collaborators who challenge ideas around the relationship to art and productivity, community integration, and authorship. Myrtle is the founder of The Beyond Strong Community–a personal and collective care community that provides multimodal arts based practices by local women artists for Black women that examines joy, ease, and liberation.