In her long career, Kathi George has edited a variety of books, from scholarly manuscripts to textbooks, trade books to fiction. After thirteen years editing Frontiers, George moved to San Diego in 1987 and as a freelancer has had such clients as Harcourt, Random House, Stanford University, ZYZZYVA, Brighton Press, Tehabi Books, Sun & Moon Press, SeaWorld, and Shambhala. She taught copy editing and proofreading in the UCSD Extension Editing Certificate Program for ten years, designing classes on literary editing, bias-free language, book production, copyright law for editors, and in-house style sheets. George is the author of “69 Workshops for Copy Editors,” published by Copy Editor Newsletter in 1994 and 1996, and for four years she wrote a column on typos called “Misspelling Cincinnati,” that was carried in the San Diego Professional Editors’ Network newsletter.

George holds a master’s degree in twentieth-century Italian literature and history from the University of Colorado and is a graduate of the Stanford Professional Publishing Program and the University of Chicago Graduate Publishing Program. Her personal papers from her years as editor and publisher of Frontiers are housed at the Schlesinger Library of Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University.

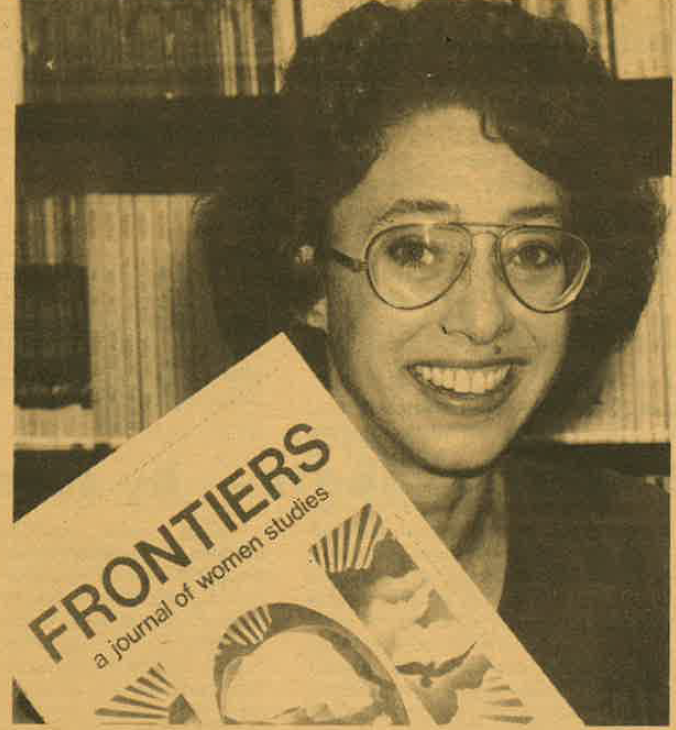

In 1974, George and her colleagues founded a Women’s Studies program at the University of Colorado-Boulder. The same group of women not only greatly expanded the program’s holdings in cutting edge Women Studies books, but they also formed a new journal called Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. As George reports in her oral history, “Alanna Preussner came up with the idea of the word Frontiers. And we meant it to be partly a new scholarship from the west and partly just the new frontiers of Women’s Studies” (George, p. 23).

The Journal was founded in the fall of 1974 and the first issue was self-published in 1975. The five founding collective members produced the Journal in a nonhierarchical labor structure while receiving no support from their university. All members were capable of performing each task that the Journal required although they discovered that this model was not sustainable in the long run.

For thirteen years, George was the main editor and publisher, although the editorial collective remained active. She worked with the Journal from 1974 to 1987. The editorial collective members came together for monthly meetings where they read manuscripts, set up policy, solicited board members, and shared meals. As George reports, she worked over forty hours a week, unpaid. In Betsy Jameson’s oral history, she notes, “The Journal owes more to Kathi George than to anybody, and that should get some recognition. I mean, she was just stubbornly dedicated to this Journal and gave more years of unpaid labor to it than you can imagine” (Jameson, p. 8).

The process of collecting manuscripts, reviewing, editing, publishing, distributing, and mailing the Journal took an extraordinary amount of work. Although Frontiers was associated with the Women’s Studies Program, it was unincorporated and therefore did not technically have an institutional home or legal status. George also was the publisher for the Journal. For many years, George would distribute the Journal to local bookstores and she found it interesting that people weren’t purchasing the Journal to read for pleasure. It became clear that Frontiers was becoming more of an academic journal despite its original design to actively attract both non-academic and academic readers.

Although the original editorial collective was made up of middle-class, highly educated white women, George asserts that there was a serious commitment to women of color, lesbians, working-class women, and non-elite white women. The oral history volumes produced during the beginning phase of the Journal’s history remains a highly valued memory. Toward the end of her tenure with the Journal, there was in-fighting among the collective and George and others determined that the model of one unpaid person doing most of the work was unsustainable. Institutional support would be found later once the Journal moved to the University of New Mexico.

Find more about Kathi here.

Selected Quotes from Frontiers at 50 Oral History Interview

“We weren’t incorporated. We weren’t a nonprofit. We weren’t part of the university, so we really had no legal status whatsoever.” (p. 24)

“We were very dedicated to turning out a very clean journal so that it would give credibility to us and to the field of Women’s Studies because when we started we were seen as not serious academically.” (p. 4)

“We did not think we were going to last. We did not think we were a permanent thing. The thought of forty-seven years of publishing was completely out of this world. We didn’t have a vision for the future. And the fact that there were these journals that became part of the university, or part of the university press journals division – that was a totally new model. That was definitely not our vision at the beginning. We really didn’t have a vision at the beginning. We didn’t think we were going to last. We were very fragile. We had no money. We had no subscriptions. By the time I left, we had still not broken through about a thousand subscribers, between individuals and institutional subscriptions.” (p. 21)

“And we did change the world. Women’s Studies, the Women’s Movement, women’s journals absolutely changed the world. And we were part of making that critical mass. We were part of making it legitimate – and now in academia there’s hardly a major university in America that doesn’t have a Women’s Studies program or some kind of department addressing Women’s Studies, Gender Studies, lesbian studies. And by publishing like we did, we helped to establish critical mass and by critical mass, acceptance and legitimacy.” (p. 33)

“One thing I wanted to talk about was the amount of content that we produced in those twenty-six issues. Over the weekend I did a page count of how many pages we produced during those twenty-six issues: 2, 682 pages approximately and an 8 ½ by 11 size, two columns per page. The average page count per issue was 103 or 104 pages. That’s a lot of copy. And we had a big commitment to women of color from day one and a big commitment to lesbians from day one and a very big commitment to community women, working-class women and nonelite white women.” (p. 123)

“And when we first started there weren’t that many Women’s Studies programs and there weren’t that many women who had faculty appointments. So, it was a much more varied group and we tried to have a variety of voices that would appeal to people who were non academically ensconced, entrenched. That went by the wayside after a while because our subscription base tended more toward the academic and our readership and the articles we were sent, the submissions we got, just became over time more scholarly and then the language that was being used in those articles became more academic. And the fact that there were, like, forty-one footnotes to, you know, a ten-page article…” (p. 28)

“We were some of the earliest publishers of articles and manuscripts and creative work by Chicanas, Native American women, Asian women, and lesbians. And also, to women in the west. And that strong commitment we held fast to during the thirteen years that I was there. That to me is the most important thing that we did.” (p. 30)

The full oral history interview video and transcript can be found at the following Frontiers archives locations:

UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library:

University of Utah, J. Willard Marriott Library:

ACCN3283 Frontiers A Journal of Women Studies Oral History Collection